“I’m gonna tell you if you have youngsters in the living room tell them not to be alarmed at this ‘cause it’s a fantasy, the whole thing is animated…”

-- Ed Sullivan introducing the apocalyptic short film A SHORT VISION on the May 27, 1956 broadcast of The Ed Sullivan Show[1]

“Years later I met a man from Canada who had shoulder length dark hair, but in the center of his head was a small spot where his hair grew out a silvery white color. I asked him about it, and he told me that he was a medically documented case of a person whose hair had turned white from fright. As a child, he had seen A SHORT VISION while alone in a house, and he experienced extreme panic and terror for some time, and one result was that his hair began to grow out white from that one spot on his head.”

-- Excerpt from a remembrance written for CONELRAD by Michael Mode, baby boomer, who also saw the end of the world on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1956[2]

INTRODUCTION: Sunday Night at the Apocalypse

From the vantage point of today’s media-saturated, 24/7, TV-in-every-room, on-demand world, the concept of a must-see, live, prime time television show starring an awkward newspaperman nicknamed “Old Stone Face” is hard to fathom.[3] Throw in the fact that the show was a bona fide institution for over two decades and the premise begins to sound like science fiction. The closest current analog to The Ed Sullivan Show in terms of popularity is FOX’s American Idol, but Idol producers would sell what is left of their souls to get Sullivan’s audience share. The proudly untelegenic host dominated Sunday nights in an era well before TV fractured into 500 channels. But today Ed Sullivan’s significance to broadcasting is practically unknown to Americans born after the baby boom generation.

Indeed, when the gossip columnist turned impresario is discussed at all these days, it is usually in reference to his undeniable impact on popular music: Sullivan hosted two of the biggest rock acts in history — Elvis Presley and the Beatles — for a series of legendary, career-making performances. But far more impressive is the fact that this unlikeliest of television stars presided over a staggering diversity of entertainment for an astounding 23 years and 1,087 hour-long shows.[4]

Sullivan’s popularity also succeeded, however inexplicably, in making the characters of Senor Wences and Topo Gigo household names. Sullivan or his persona is also vaguely known by America’s post-boomers because of the caricature that outlived the man: the hunched shoulders, the catch phrase (“A Rilly Big Shew”) and the numerous impressions that were done of him — many by comedians on his own show.[5]

The program was not all rock and roll and hand-puppets, however. Over the years, in addition to the usual rotation of pop musicians, jugglers, trained animals and comedians, Sullivan threw a few highbrow curveballs at his audience like poet Carl Sandburg, artist Salvador Dali, opera star Maria Callas and ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev among many others.[6]

On May 27, 1956 the host threw more than just a curveball: he broadcast an animated short film about the end of the world that still reverberates within the memories of an untold number of baby boomers.[7] The movie, A SHORT VISION, and its exhibition on The Ed Sullivan Show, came to the attention of CONELRAD a number of years ago when we worked with Laura Graff on her posted testimony about the civil defense dog tags that she wore as an elementary school student in the Fifties.[8] It was clear from speaking with Ms. Graff at the time that the film was one of those jolting childhood experiences that one never completely shakes. We were intrigued, but in classic CONELRAD fashion it took us a long time to follow up adequately.[9]

In the years since Ms. Graff shared her recollections with us, we have heard from other baby boomers about this “terrifying” and “strange” unnamed film — frequently the people who contact CONELRAD do not even know the movie’s title, just that they remember seeing it--or parts of it--on television (Ms. Graff didn’t know the title either until we told her). A SHORT VISION has been discussed on at least one blog with a similar air of semi-recovered memory mystery.[10]

The primary purpose of this article then is to present the rich history of a remarkable film so that it is no longer shrouded in a haze of uncertain recollection. Another goal we hope to achieve by posting this comprehensive feature is that more people will come forward with their unique memories of seeing A SHORT VISION back in 1956. A sidebar to this article presents the testimony of several baby boomers who remember watching the film on Sullivan. Given The Ed Sullivan Show’s immense viewership, there must be many more people out there.

In the course of our research for this feature, CONELRAD obtained a color copy of A SHORT VISION from the National Archives in College Park, Maryland (a 16mm print of the decidedly anti-war movie is stored, ironically enough, in the FEMA records group). This print, an American distribution copy with the credit “George K. Arthur Presents,” is not of the best quality, but it served our limited purposes. As we were preparing to post this article we were delighted to see that the British Film Institute had finally succumbed and posted their pristine color print on YouTube.[11]

It is easy to see how even a black and white broadcast version of A SHORT VISION could traumatize a generation of children who were accustomed to the benign animated fare of Eisenhower-era kiddie shows: it depicts a phantom object from the sky decimating all life below with a giant fireball. And to be fair to the baby boomers, the melting faces sequence would probably freak out today’s most sophisticated five-year-old, too.

The Fifties kids were also at a psychological disadvantage because of the way Sullivan soft-pedaled his first parental advisory: “I’m gonna tell you if you have youngsters in the living room tell them not to be alarmed at this ‘cause it’s a fantasy, the whole thing is animated…”[12] As we will quote in full later in this article, the host would strengthen his warning considerably when he ran the film a second time two weeks later.

ORIGINS OF A SHORT VISION: The Artists and the Showman

Peter Foldes, the primary creative force behind the film that so unsettled Ed Sullivan’s young audience, was born in Budapest, Hungary in 1924. He moved to England shortly after World War II to study at the Slade School of Art and at the Courtland Institute where he met fellow student and future wife, Joan, also born in 1924.[13] In Britain, during these early years, Mr. Foldes worked with fellow Hungarian John Halas on his animated films.[14]

It should come as no surprise to anyone who has seen the wonderfully layered renderings that populate A SHORT VISION that Peter Foldes made his mark in the fine arts world before becoming more dedicated to film. This 1949 London Times review documents one of his early exhibits:

The abstract paintings of Mr. Peter Foldes at the Hanover Gallery, 32a, St. George’s Street, are highly decorative, not to say ornate, and many of them contain a profusion of small and attractively colored patterns, arranged with much taste and tact. Moreover, he continually varies the surface and quality of the paint, so that a single picture might serve as a collection of the painter’s samples, and at times he has indulged in such minute elaboration of some compartment of a picture that this asks to be separately inspected as if it were a detached ornament. Nevertheless, he makes a real effort to impose order on this multiplicity of decoration and usually succeeds in keeping clear the main emphasis and balance of the design.[15]

Including their 1956 masterpiece, A SHORT VISION, the Foldes team made four short films together as well as a few publicity (or advertising) films.[16] Based on this account from the 1973 book The Animated Film by Ralph Stephenson, their very first short film, ANIMATED GENESIS (1952), shares some thematic and artistic touches with A SHORT VISION:

It starts off with blue shapes, atoms, water rippling and reflecting, cell structures, branching growths, then a great spider (evil) chasing a moth (good). The spider enslaves tiny Egyptian human beings, the moth brings them scientific inventions (tractors, machines and so on) which the spider turns to destructive purposes. Finally the giant spider is blown up by his own bomb and the world becomes a modern utopia.[17]

AMERICAN GENESIS was funded by a grant by the British Film Institute and it went on to win the Prix pour la Couleour award at the Cannes Film Festival in 1952.[18] The best was yet to come.

In a rare interview, Joan Foldes described for CONELRAD the circumstances that led to A SHORT VISION being made:

The poem [theme / story] that runs through A SHORT VISION was Peter’s. He came up to me on the ship that was bringing us back from Australia in October, 1954. He asked me what I thought of it. I said we HAD to do it. He was the creative artist; otherwise it was the same as for AMERICAN GENESIS. I helped in setting up the stand, deciding on some of the figures, the timing of the animation lighting, and the easier part of the animation.[19]

A passage in the 1966 book The Living Screen by Roger Manvell reveals the additional detail that A SHORT VISION was produced in the Foldes’ kitchen.[20] A screen credit at the beginning of the British print indicates that the film was “completed with the support of the the British Film Institute’s Experimental Film Fund.”

Before the film made its spectacular splash on the American side of the pond, it was shown at the National Film Theatre in London and reviewed on January 26, 1956 in the London Times under the headline “Cartoon of the End of the World”:

A SHORT VISION, made by Joan and Peter Foldes, has little animation. It is rather a series of powerful, static drawings dissolving to show the death and consumption of all living things at the explosion that brings about the end of the world; it is a work of sombre imagination.

According to an article in the May 28, 1956 edition of the New York World-Telegram and Sun it was in England where Ed Sullivan first saw A SHORT VISION and where he “resolved to give it an American premiere.” The newspaper added that Sullivan’s motive for airing it was a “plea for peace” and quoted the host as saying “I figured with the H-bomb just being let go of last week it was apropos.” An Associated Press dispatch from May 29, 1956 reported that Sullivan viewed A SHORT VISION “10 days ago in England.”[21]

Besides his professed desire to aid world peace, Sullivan may have decided to run the film for a more realistic reason — he had a business relationship with its U.S. distributor, the colorful showman George K. Arthur. Indeed, a brief story in the May 29, 1956 edition of the trade paper the Hollywood Reporter noted that A SHORT VISION was “the sixth film that George K. Arthur has imported and sold to TV as well as theaters. In all he has realized close to $100,000 from the TV rights to the six films which have been shown on big network programs. His next short, Marcel Marceau’s ‘In the Park,’ will also be seen on Ed Sullivan’s show this fall, two weeks after its theatrical premiere.”[22]

It should be pointed out here that Sullivan had single-handedly pioneered the practice of promoting films on television, so it was not unusual for him to air long clips from movies on his show. On one broadcast he devoted 30 minutes of airtime to advertise GUYS AND DOLLS (1955).[23] In this context and with the background on Sullivan’s connection to Arthur, it becomes easier to understand how an avant-garde 6-minute animated film was allowed on the air. To be fair, though, the host’s evolving Cold War attitudes may have also played a part in his deciding to run what one media outlet labeled an “anti-war cartoon.” Sullivan began the the Fifties as a dependable Red-baiting, blacklist-enforcing anti-Communist (with a major detour in 1952 to attack Senator Joe McCarthy in his newspaper column), but by the end of the decade he had taken his show to Cuba to meet the not-yet-declared Communist Fidel Castro and to the Soviet Union where the host opened a humanizing window on Russian life. So it is not that big a stretch to believe that by 1956 Sullivan’s view of the superpower struggle was changing and that he would be willing to screen a pacifistic cautionary tale for his audience.[24]

Regardless of the true motivations to air A SHORT VISION, it was still a bracingly odd programming choice for the guardian of America’s living room. Based on Sullivan’s original on-air comments, the fact that it was animated seemed to make it acceptable in his mind to show. As evidenced by broadcasts that would air within a year after A SHORT VISION, it would seem that Sullivan and his team cared less about the disturbing content of a “cartoon” than they did the potential live action landmines of Elvis Presley’s hips and Jayne Mansfield’s bust.[25]

George K. Arthur (aka George Brest) was a Sussex, England born Hollywood comedy star of the Twenties and Thirties who reinvented himself in the Fifties as a producer and distributor of short subject movies.[26] According to Joan Foldes, she and her husband met with him on several occasions in Paris to discuss their work.[27] Arthur’s 1957 oral history for Columbia University does not mention A SHORT VISION or the Foldes, but it does help explain how he made a success of his second show business career:

There’s no money, really, in shorts. Nobody seems to want them, and then they give such a small amount of money for them. So what happened, I lived at home for two years working out of my bedroom as an office—combination bedroom and office, and then eventually I got five or six [shorts] together, and somebody else came to me and said, “We’d like you to distribute a couple.” And that’s the way somehow we got off the ground.

Now, we’ve got forty of them. And last year [1956] we got an Oscar for THE BESPOKE OVERCOAT, which was a nice play. And of course now we’re an established business; we have all these shorts, and now they pay.[28]

A SHORT VISION’s American debut on the May 27, 1956 broadcast of The Ed Sullivan Show probably came off exactly as planned for Mr. Arthur, but it apparently caught Peter and Joan Foldes off-guard. “As far as I remember we were both very surprised when we heard about it,” Joan recalled for CONELRAD. “I imagine it [being shown on Sullivan] must have been through George…”[29]

The guests that night, according to a TV listing in the Los Angeles Examiner, were “Kate Smith; Marion Marlowe, Senor Wences, ventriloquist; comedian Dick Shawn; English singer David Whitfield; winners of the Harvest Moon dance contest and the Hasleves, acrobats.” There was no mention of any short subject film in the Examiner or any other newspaper listing that CONELRAD looked at.[30]

Through the generosity of Andrew Solt — whose company SOFA Entertainment, owns the rights to The Ed Sullivan Show archives — CONELRAD was able to view both the May 27, 1956 and June 10, 1956 clips that featured A SHORT VISION. It is fascinating to see how Sullivan handles the pre and post screening comments. As previously mentioned, the host was less than adamant in his parental caution on the initial broadcast. Here, verbatim, are his introductory remarks before showing what was about to become a very controversial film. Sullivan opens his comments with a timely reference to the first hydrogen bomb to be dropped from an American airplane — a feat that was trumpeted from the front pages of newspapers across the country earlier in the month of May 1956.[31]

Just last week you read about the H-bomb being dropped. Now two great English writers, two very imaginative writers — I’m gonna tell you if you have youngsters in the living room tell them not to be alarmed at this ‘cause it’s a fantasy, the whole thing is animated — but two English writers, Joan and Peter Foldes, wrote a thing which they called ‘A Short Vision’ in which they wondered what might happen to the animal population of the world if an H-bomb were dropped. It’s produced by George K. Arthur and I’d like you to see it. It is grim, but I think we can all stand it to realize that in war there is no winner.

After the film concludes, Sullivan is standing on the stage looking knowingly at his deadly silent audience. There is then some nervous laughter as he smiles and says “See” while nodding his head (as if to say, “I told you so”). And then, without missing a beat, the host shifts back to MC mode:

Ladies and gentlemen, here is this brilliant young English singer. We brought him over, two years ago, David Whitfield, because of his recording of ‘Cara Mia.’ Now he’s going to sing a song from MY FAIR LADY. David Whitfield, let’s have a very big hand for David.

Whitfield then comes out and starts singing “On the Street Where You Live.”[32]

It is important to note that Sullivan’s characterization of the Foldes’ film as concerning the effects of an “H-bomb” is not strictly accurate. The film’s biblically flavored allegorical narration avoids any modern references. But then again the point of the movie is hard to miss. There is, after all, a plane-like object that flies overhead and leaves a mushroom cloud-like fireball in its wake. Sullivan’s description of the story as being about the impact of an “H-bomb” on the “animal population” is narrower than what is actually depicted in the film (by the final frame of the movie, all life – animal, human and insect — is extinguished). Sullivan’s remark might lead some to think that he did not watch the entire film before airing it on his show.

FALLOUT AND REPRISE

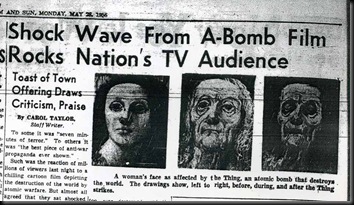

The day after A SHORT VISION was shown on The Ed Sullivan Show to what was reported as a 37.2 in the ratings,[33] the New York World-Telegram and Sun ran on its second page the blaring headline “Shock Wave From A-Bomb Film Rocks Nation’s TV Audience.” And if the headline wasn’t enough, just below it was a gruesome three-panel graphic from the face melting sequence. The article was written by Carol Taylor in classic tabloid style and it is so entertaining (if not entirely accurate) that it is worth presenting here in its entirety. When reading the text pay attention to how Sullivan misrepresents to the reporter how he tried to protect the “youngsters.” The host was fortunate not to live in the era of TiVo and the Internet.

To some it was “seven minutes of terror.” To others it was “the best piece of anti-war propaganda ever shown.”

Such was the reaction of millions of viewers last night to a chilling cartoon film depicting the destruction of the world by atomic warfare. But almost all agreed that they sat shocked and spellbound as people were disintegrated before their eyes. It was shown on Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town on CBS television [editor’s note: Sullivan changed the name of his program from Toast of the Town to The Ed Sullivan Show in 1955].

Mr. Sullivan told this newspaper today that that calls are pouring in, both to his own office and the network, and, that in response to many requests, he will repeat the showing on his June 10 show.

He said several people on his show warned him that it was “too grim” for TV consumption before the film was run last night. But, he explained, he considered it a powerful plea for peace and “I figured with the H-bomb just being let go of last week it was apropos.”

The toastmaster said he saw the film in England where it received rave notices from such papers as the London Times and Manchester Guardian. He resolved to give it an American premiere. It was made by a young husband and wife team, Peter and Joan Foldes, who won first prize at the Cannes Film Festival for their first cartoon, “Animated Genesis,” a history of evolution.

The austerely drawn film is narrated in a calm British voice. The voice tells of a “Thing which, as it flies overhead, burns everything living into a skeleton and at last destroys itself.”

As the Thing comes swiftly, noiselessly, irresistibly, animals, who see it first, are so terrified (or compassionate) that they release their captives. The owl looks up and the rat runs free from its clutching claws. The deer darts free from the leopard’s grasp.

Then the bomb explodes in midair.

The people are asleep and faces of children and adults are shown in repose. In stages the faces change to skeletons. “Their leaders looked up and their wise men looked up, but it was too late.”

All who saw it, the people and the animals, were destroyed. “When it was over, there was nothing left but a small flame. The mountains, the fields, the city and the earth had all disappeared, and it was cold, except for the small flame.”

Spines tingle for a moment as the eerie flame glows—“and then I saw it, still flying around the flame. And now it looked like a moth and it, too, was destroyed, and the flame died.”

Mr. Sullivan said he deliberately showed the eerie cartoon just before sign-off “figuring that youngsters should have been asleep anyway,” but he warned that it “wasn’t for youngsters.” Many small fry, of course, took a peak anyway and the MC braced himself for a barrage of squawks from mothers about the gruesome “bedtime story.” As one father said, “Sullivan’s always billing ‘something for the kids.’ This was kind of rough.”

He said wires and phone calls take the turn either “Thanks for having the guts to run it” or “It was a terrifying thing to do.” The show’s rating was 37.2 against NBC’s 7.2.

The film will be distributed commercially here in the fall by George K. Arthur, producer and distributor, 654 Madison Ave. The critic of the London Times said of it “In five minutes I was more persuaded than in ten years since Hiroshima.”[34]

The next day, Tuesday, May 29th, an Associated Press story on the controversy ran in newspapers nationally. One newspaper headlined the A.P. article as “Ed Sullivan A-Film Shocks Viewers” and contained the lead: “Ed Sullivan slipped a chilling shocker in at the end of his television show Sunday night—a short cartoon showing the end of the world by atomic warfare.” The story goes on to report “heavy reaction,” pro and con, coming in at CBS.[35]

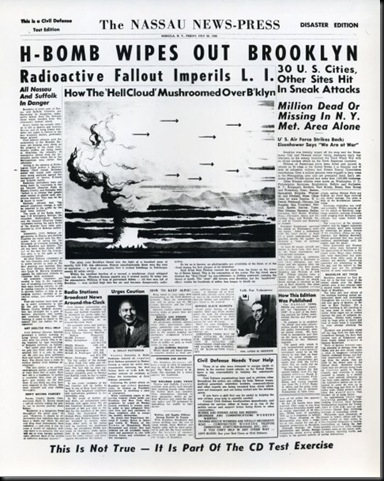

On May 30th, the editorial staff of the Post-Standard in Syracuse, New York published a piece entitled “Anti-War Document” that praised Sullivan for airing A SHORT VISION. It is such a compelling commentary that we are presenting it here in full:

The cartoon film on the Ed Sullivan television show which has caused so much comment is an effective method of bringing home the stark reality of atomic warfare.

This short fantasy made in England gains power through its very simplicity. Perhaps no other medium could convey the finality of such conflict.

It shows the reaction of humans, animals and birds, and the measured narration heightens the inevitability of destruction.

Arguments against showing of the film, which Sullivan plans to present again June 10, are outweighed by the necessity of portraying in some graphic form such as this the true meaning of another war.

It should be shown all over the world, particularly in Russia. It is the best argument for peace at any price that has been presented in a long time.

Shocked public reaction was natural, but the impact is more one of grim realization than terror, and one viewer put it precisely when he said it is the best piece of anti-war propaganda ever shown.[36]

Walter Ames of the Los Angeles Times wrote in his May 31st column that “Smiley [another one of Sullivan’s nicknames] told me that he received such an enormous amount of mail on his showing of the British short, ‘A Short Vision,’ that he’ll repeat it on his June 10 show…”[37]

In its “Week in Review” section dated June 11, 1956, Time magazine took note of the atomic hullabaloo: “Even in black and white, the Vision was so chilling that the studio audience sat in stunned silence when it was over. Wires and phone calls poured in, about evenly divided between praise and condemnation…”[38]

Curious to see if any of this viewer mail concerning A SHORT VISION survived, CONELRAD contacted CBS Audience Services Director Ray Faiola. Mr. Faiola informed us via e-mail on March 19, 2009 that “Viewer correspondence from this period has been long-destroyed.”[39] Undeterred we contacted an archivist for the Ed Sullivan Papers at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research (part of the Wisconsin Historical Society) and learned that in the folder for the May 27, 1956 broadcast, there was only a draft of a script unrelated to the film — no letters or even newspaper clippings on the controversy.[40] Finally, we reached out to Sullivan biographer James Maguire who informed us that he was completely unaware of the “Short Vision” controversy. In fact, none of the Sullivan biographies reference A SHORT VISION.[41]

Unlike its stealth airing on the May 27, 1956 broadcast of the Sullivan Show, A SHORT VISION was heavily promoted in newspaper programming highlights and television listings for its June 10th reprise. The TV Guide listing, for example, put the Foldes film up front:

8:00 ED SULLIVAN—Variety

In answer to popular demand, Sullivan will show again the animated fantasy “A Short Vision,” which depicts abstractly the effects of the H-bomb. On the guest list tonight: singer Nat “King” Cole; dancer Carol Haney; comedian Jack Carter; ventriloquist Ricky Layne and his dummy Velvel; Edith Adams, who repeats her imitation of Marilyn Monroe; rock ‘n’ roll singer Joey Clay; the Half Brothers, jugglers. A filmed sequence starring Bob Hope is also featured.[42]

All of Sullivan’s biographers agree that he had a genius for publicity. He was, remember, a gossip columnist who was skilled at milking a good story.[43] This helps explain why Sullivan decided almost immediately to run the film again on his show – he wanted to capitalize on the press stories that he knew were coming. So it was that the gangly host appeared on his stage the night of June 10th proudly clutching a newspaper and a magazine as he launched into his reintroduction of A SHORT VISION (and this time he made the parental advisory as strong as possible):

Two weeks ago on this program I put on a film — an animated film — about the atom bomb. And the first tremendous reaction came from the World-Telegram, New York — three column story, ‘Shock Wave from A-Bomb Film Rocks nation’s TV Audience’ by Carol Taylor. And I notice in Time this week, they have a big story on it. So, tonight, in answer to requests from civil defense bodies[44] from all over the country, I’m going to show the film again, but for those of you who have youngsters in your living room, it is a harrowing experience for youngsters, so would you please take them out of the room and just have the older people in the family look at it. I think its something the country should know, should see, but the youngsters, that is the little ones, should not be looking at it. So now if they’re out of the room, here is this film, by two young Britons on the possible repercussions of an A-bomb. George, may I have it? [Film starts]

After the film concluded Sullivan offered a poignant personal story before shamelessly segueing to the Navy Blue Angels who were sitting in the studio audience that evening:

You know, a little boy last week, after he had seen it—by accident—he asked his dad, who is Marlo Lewis, he said, “Daddy, was God destroyed, too?” His father explained to him that God wasn’t destroyed and this was all fantasy and, of course, God never is destroyed and always looks out for little boys. But they’re some men out in the audience and I know they’re particularly interested in this short, “A Short Vision” by Joan and Peter Foldes, because they are the famed Blue Angels of the United States Navy. They’re the fliers who fly these precision formations—how they do it no one’s ever been able to figure out—but they’re celebrating their tenth anniversary and I’m going to ask them to stand up with their commanding officer, Richard L. ‘Zeke’ Cormier. The Navy Blue Angels, will you all stand up, please. [Audience applause].[45]

The little boy’s father referenced in Sullivan’s remarks is the original producer of the Ed Sullivan Show (from 1948 to 1960), Marlo Lewis who passed away in 1993.[46] And the little boy mentioned by Sullivan, CONELRAD discovered, is Marlo Lewis, Jr., now a senior fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute. Mr. Lewis was kind enough to talk to us about his involvement in A SHORT VISION history after viewing a copy of the film that we provided. Lewis stated to us that he would have been 5 and ½ when these particular programs aired.

“We watched the Sullivan Show every Sunday night. It was like a ritual, so I almost certainly saw the film. I can’t swear that I never saw it. Some of it brought back certain images [in my memory]. I kind of remember the fly or the airplane, the thing that drops the bomb. And the animal faces. I had the feeling I had seen it before, a kind of familiarity.”

On the matter of whether he would have asked the question of his father attributed to him on the air by Sullivan, Lewis replied that it was around this time that he started posing “questions of power” to his parents (e.g. “Could ten angels beat up God?”), “so, it is very plausible that I asked [the question regarding God being “destroyed” in the film].” However, Lewis does not explicitly remember making the inquiry. Quite understandably, he has a much clearer memory of meeting Paul McCartney after seeing the Beatles rehearse before one of their historic Sullivan appearances in 1964.[47]

After the June 10, 1956 broadcast, the reaction to the encore of the film was confined to the trade papers. The following are excerpts from reviews of the show:

Sullivan reprised the cartoon, “A Short Vision,” a warning on atomic warfare. A bit grisly, he rightfully warned parents to get the kids out of the way.

-- Jose., Variety, June 13, 1956

Repeat of last week’s (by popular demand) English short “A Short Vision” scored a somber but effective note with crude semi-moving drawings of H-Bomb effect especially realistic as we watched victim’s faces slowly disintegrating into skeleton masks.

-- The Hollywood Reporter, June 12, 1956

After the hubbub of The Ed Sullivan Show airings dissipated, A SHORT VISION went on to a modest theatrical release in the United States where it was favorably reviewed. The New York Times called it “a beautiful and bloodcurdling little animated picture” and cautioned that it was “admirable but not for the meek.”[48]

The Monthly Film Bulletin in England published a lengthier review in its July 1956 issue:

The Vision depicted in this short cartoon is that of atomic destruction. A "Thing" suddenly appears in the sky, flying over countryside and cities, and destroys all living things. All that finally remains is a single flame with a moth fluttering around it; and, after a moment, the flame devours the moth...

Employing a simple animation technique, A SHORT VISION creates an imaginative and disturbing picture of atomic warfare and (understandably) caused something of a furore when shown on American television recently. The horror of the subject is presented quite unflinchingly, the film's attitude being summed up in some terrible close-ups of decomposing faces. These images are reinforced by a coldly forceful commentary and some slightly inappropriate "science fiction" music. Whether one responds to the style or not, the film clearly reveals the deeply felt convictions of its makers.[49]

Before its retirement to Cold War pop culture history and hard-to-find 16mm Encyclopedia Britannica prints,[50] A SHORT VISION won the prize for best experimental film at the 17th Venice Film Festival in September of 1956.[51] From this point forward, outside of a few mentions in film books and websites, it has mostly existed in the buried thoughts of American baby boomers. As of the posting of this article, A SHORT VISION did not have an entry on the Internet Movie Database or Wikipedia.[52]

Peter Foldes returned to his abstract painting career for the next decade in Paris while continuing some efforts in animation. “Un Garcon plein d’avenir” (A LAD WITH A FUTURE) won a special jury prize at the Sixth Annual Film Festival in Annecy, France in 1965. The London Times (which referred to it as “A Boy with a Future”) called it “a brilliantly drawn evocation of the aggressive instinct in man.” In 1964 he created the short film EATING LIKE A BIRD and in 1967 he produced a video short about the battle of the sexes, FASTER. In 1969 he made the film I, YOU, THEY.

With Rene Jodoin, head of the National Film Board of Canada’s French Animation Studio, Foldes became the first filmmaker to use computer animation, a system called “key frame animation.” Foldes’ METADATA in 1971 was the first “computer-animated short involving free-hand drawings.” HUNGER, which Foldes co-produced in 1974 with Jodoin, was a more sophisticated second effort in computer animation. It was an 11-minute short concerning poverty and became the first computer animated film to earn a Best Short Subject Oscar nomination. For a brief period around this time (1974), Foldes also drew a comic strip called “Lucy.” [53]

Foldes won the 1978 Cesar Award in France for the short animated movie, REVE, which was released in 1977, the year of his death.[54] The 1977 Cannes Film Festival, which occurred several months after Peter’s passing, held a special homage for his body of work in animation.[55]

Joan Foldes, who divorced from Peter at some point along the way, remarried and now lives in Paris where she writes poetry.[56] George K. Arthur, the man who helped get A SHORT VISION on The Ed Sullivan Show, died in 1985. James McKechnie, the actor who provided the calm British-accented narration of A SHORT VISION died in 1964. Matyas Seiber, the Budapest-born composer responsible for the haunting music heard in the film passed away in 1960.[57]

Ed Sullivan hosted a few TV specials and continued to write his “Little Old New York” column for the New York Daily News after his beloved show was cancelled by CBS in 1971. The television pioneer and icon died of esophageal cancer at the age of 73 on October 13, 1974 (a Sunday).[58]

A SHORT VISION LEGACY PROJECT

Since 1956 A SHORT VISION has been kept alive in the pages of film and animation books and, more recently, on a few websites. As mentioned before, the short film and its controversial network airings somehow managed to elude all of the otherwise thorough Sullivan biographers.

The movie has also lived on in the memories of countless numbers of kids who ignored Ed Sullivan’s warnings and watched the scary “cartoon” back in ‘56. In preparing this article CONELRAD sought out several of these SHORT VISION veterans for their stories. We have posted this first set of recollections on a separate page on the hunch that there will be more to come. Indeed, we hope that these initial remembrances encourage many more people to write in. We are particularly interested in hearing from the poor chap referred to in Michael Mode’s essay who sprouted white hair from fright.

The October 14, 1974 New York Times obituary for Ed Sullivan estimated that between 45 and 50 million people tuned in to his show each week. There is no way of knowing how many children watched A SHORT VISION, but based on the Times’ overall number and because the film was aired twice, we’re guessing that we’ll be posting remembrances for quite some time to come.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted first and foremost to Laura Graff for mentioning to us her childhood SHORT VISION memory. Without her recollection (and the ones that followed from other baby boomers), we probably would not have endeavored to do this article.

CONELRAD is extremely grateful to Andrew Solt and SOFA Entertainment for permitting Bill Geerhart to view the two SHORT VISION clips from The Ed Sullivan Show broadcasts. It was an invaluable aid to our research to be able to see how Sullivan presented the film. And thanks to Ed Sullivan Show producer Robert Precht for believing in the worthiness of our mission.

CONELRAD would also like to thank Joan Foldes for her willingness to comment on her film. We would love to conduct a lengthier interview with Ms. Foldes someday if she is willing. Thanks, too, to Mathieu Foldes for his help in coordinating our interview with his mother.

Thanks to Marlo Lewis, Jr., the son of original Sullivan Show producer Marlo Lewis, for taking the time to speak with us about his childhood memories regarding A SHORT VISION.

Finally, thanks to Ed Sullivan biographer James Maguire for responding to our inquiries on several points regarding the host’s life and career. Maguire’s book Impressario is a great resource to have in learning about the history of the Sullivan show.

Another excellent resource is A Really Big Show: A Visual History of the Ed Sullivan Show with text by John Leonard. A highlight of this book is the end section that provides a selected list of the ten thousand performers who appeared during the program’s 23-year history and the number of times they appeared. The Beatles made a total of 10 appearances including 7 that were taped.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

CONELRAD relied upon the following reference works and resources in researching this article.

CREDITS

George K. Arthur PresentsA SHORT VISION

Written, Designed and Produced by

Joan and Peter Foldes

Music Composed by Matyas Seiber

Commentary Spoken by James McKechnie

BOOKS

Always on Sunday: Ed Sullivan: An Inside View

1968

Michael David Harris

New York: Meredith Press

215 Pages

The Animated Film

1973

Ralph Stephenson

London: Tantivy Press

Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan

2006

James Maguire

New York: Billboard Books

344 pages

The Living Screen: Background to the Film and Television

1961

Roger Manvell

London: George G. Harrap & Co., Ltd.

192 Pages

Nuclear War Films

1978

Edited by Jack G. Shaheen

Chapter 13: War in Short by William Meyer (pages 89-90)

Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois Press

193 Pages

Prime Time

1979

Marlo Lewis & Mina Bess Lewis

Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher, Inc.

256 Pages

A Really Big Show: A Visual History of the Ed Sullivan Show

1992

John Leonard

New York: Viking Studio Books

255 pages

Sundays with Sullivan: How the Ed Sullivan Show Brought Elvis, the Beatles and Culture to America

2009

Bernie Ilson

Lanham, MD: Taylor Trade Publishing

216 Pages

A Thousand Sundays: The Story of the Ed Sullivan Show

1980

Jerry Bowles

New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons

229 Pages

Who’s Who in Animated Cartoons: an international guide to film & television's award-winning and legendary animators

2006

Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Corporation

Jeff Lenburg

381 Pages

NEWSPAPERS / MAGAZINES

“Abstract Paintings,” the London Times, February 5, 1949

“Anti-War Cartoon to Repeat on TV,” the Hollywood Reporter, May 29, 1956

“Anti-War Document,” the Post Standard (Syracuse, NY), May 30, 1956

“Arthur’s New Art: Former Actor Triumphs in Short Film Field,” the New York Times, January 19, 1958

“B52 Air Drop of H-Bomb Termed Success,” the Associated Press via the Albuquerque Tribune, May 21, 1958

“Cartoon of the End of the World,” London Times, January 27, 1956

“Ed Sullivan, 73, Dies in N.Y.; Columnist Among First TV Hosts,” Variety, October 16, 1974

“Ed Sullivan A-Film Shocks Viewers,” the Associated Press via the Independent (Long Beach, CA), May 29, 1956

“Ed Sullivan is Dead at 73; Charmed Millions on TV,” the New York Times, October 14, 1974

“Ed Sullivan, Pioneer TV Host and Columnist, Dies of Cancer,” the Los Angeles Times via Associated Press, October 14, 1974

The Ed Sullivan Show listing, the Los Angeles Examiner, May 27, 1956

The Ed Sullivan Show listing, the Los Angeles Examiner, June 10, 1956

The Ed Sullivan Show listing, TV Guide, week of June 9-15, 1956

“Ed Sullivan’s Death Marks End of TV Era,” the Los Angeles Times, October 15, 1974 by Cecil Smith

“Ed Sullivan’s Shocker Frightens TV Viewers,” the Associated Press via the Post Standard (Syracuse, NY), May 29, 1956

“Ed Sullivan Show Review,” the Hollywood Reporter, June 12, 1956

“Ed Sullivan Show Review,” Variety, June 13, 1956 by Jose.

“Experimental Films: Cartoon of the End of the World,” the London Times, January 27, 1956

“Film Maker Sponsor of 38 Prize Pictures,” the Los Angeles Times, March 17, 1956

“Football in Art: Competition Works on Show,” the London Times, October 21, 1953

“Greek ‘Find’ at Venice Film Festival,” the London Times, September 4, 1956

“Ideas on Film,” the Saturday Review, July 6, 1957

“Marlo Lewis is Dead; TV Producer Was 77,” the New York Times, June 10, 1993

“Narrative Painting of Today,” the London Times, June 14, 1963

“Newcomers in 16mm,” the New York Times, October 21, 1956 by Howard Thompson

“Of Local Origin,” the New York Times, June 30, 1956

“Prize Winners,” the Los Angeles Times, June 2, 1977 by Charles Champlin

“Radio, TV Highlights,” the Winnipeg (Canada) Free Press, June 9, 1956

“Shock Wave from A-Bomb Film Rocks Nation’s TV Audience,” the New York World-Telegram and Sun, May 28, 1956 (many thanks to Michael Ravnitzky securing this clip for us).

A Short Vision review, the Monthly Film Bulletin (published by the British Film Institute), Vol. 23, No. 270, July 1956

A Short Vision theatrical release advertisement, the North Adams (Massachusetts) Transcript, August 30, 1956

A Short Vision theatrical release advertisement, the Berkshire (Massachusetts) Eagle, September 1, 1956

“A Short Vision to be Shown Over Channel 13 Again Today,” the Sunday News and Tribune (Jefferson City, Missouri), June 10, 1956

“Sunday TV Picks,” the Nonpareil (Council Bluffs Iowa), May 27, 1956.

“Television Highlights,” the Winnipeg (Canada) Free Press, June 23, 1956

Television listing for The Ed Sullivan Show, the Los Angeles Examiner, May 27, 1956.

“Television Programs,” New York Times, May 27, 1956

“Thousands Pay Final Tribute to Ed Sullivan,” the Los Angeles Times via United Press International, October 17, 1974

“Trends in Animated Films Today,” the London Times, February 11, 1960

“The Week in Review,” Time magazine, June 11, 1956

“Today’s Best On TV,” Mansfield, Ohio News-Journal, May 27, 1956

TV Log, Oakland Tribune, May 27, 1956

“Wide Range in Mood and Style at Festival of Short Films,” the London Times, June 29, 1965

Walter Ames column, Los Angeles Times, May 27, 1956

Walter Ames column, the Los Angeles Times, May 31, 1956

ORAL HISTORY

Interview with George K. Arthur, Fall, 1957

The Oral History Collection of Columbia University

VIDEO

The Ed Sullivan Show: A SHORT VISION clips (May 27, 1956 and June, 10, 1956), courtesy of SOFA Entertainment (Black and White).

A Short Vision (16mm American distribution copy - Color)

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland

Record Group 311: Records of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, 1956-2005

311.80 9

A Short Vision (British Film Institute copy - Color)

Posted on YouTube on May 19, 2009 by BFI Films

(See Online Resources)

Note: The Library of Congress’s Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound (MBRS) Division maintains “master material” of what they describe in their Collection Overview as “all 1,030 hours” of The Ed Sullivan Show programs. This number would seem to fall 57 hours short of the usually cited 1,087 hours that The Ed Sullivan Show was on the air. Whatever the explanation for the discrepancy in hours, the odds are that the MBRS has both the May 26, 1956 and June 10, 1956 broadcasts featuring A SHORT VISION. Therefore, because these two shows are not commercially available, members of the public interested in seeing A SHORT VISION in the manner in which it was presented by Ed Sullivan would need to get in touch with the Library of Congress to schedule a viewing.

ONLINE RESOURCES

A Short Vision: Complete Color Version of Film on YouTube

A Short Vision: BFI ScreenOnline entry

A Short Vision: Big Cartoon Database entry

A Short Vision: Animation Magazine “Question of the Week” Message Board Discussion

A Short Vision: Encyclopedia of Fantastic Film and Television entry

A Short Vision: Tate Britain Screening entry

Peter Foldes: Internet Movie Database entry

Peter Foldes: Cannes Film Festival entry

Joan Foldes: Cannes Film Festival entry

James McKetchnie Internet Movie Database entry

Matyas Seiber Internet Movie Database entry

[1] CONELRAD was able to the view the relevant clip from the May 27, 1956 broadcast of The Ed Sullivan Show thanks to the generosity of Andrew Solt and SOFA Entertainment.

[2] See Michael Mode, “Sense of Panic,” March 22, 2009, CONELRAD.com, “A Short Vision Legacy Project” sidebar.

[3] James Maguire, Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan (New York: Billboard, 2006), p. 18 for “Old Stoneface” nickname.

[4] Ibid. p. 297. Note the number of Ed Sullivan Show seasons (23) and programs (1,087) as cited in Maguire’s biography is also cited in John Leonard, A Really Big Show (New York: Viking Studio Books, 1992), introduction section.

[5] Leonard, A Really Big Show, p. 60; Maguire, Impresario, p. 164-165. There were many entertainers over the years that performed Ed Sullivan impressions on Sullivan’s own show including Frank Gorshin, Jack Carter, John Byner, Rich Little, but Will Jordan was the first and he made a career out of it – playing Sullivan in five feature motion pictures and one television movie. Per Maguire, Jordan developed his Sullivan act in nightclubs and coined the catch phrase “really big show” pronounced “rilly big shew.”

[6] Leonard, A Really Big Show, pp. 252-255

[7] Ed Sullivan Show television listing, Los Angeles Examiner, May 27, 1956. CONELRAD’s evidence that A SHORT VISION still resonates with baby boomers is purely anecdotal and based on the small number of people we have spoken with in preparing this article and the small number of people who have contacted us over the years with regard to the film.

[8] Laura Kunstler Graff, “Sirens, Dog Tags and P.S. 11: A Brief Cold War Remembrance,” CONELRAD.com, July 21, 2003; in this remembrance Graff refers to the unsettling experience of seeing A SHORT VISION (by description, not by title).

[9] CONELRAD’s Bill Geerhart first learned of the existence of A SHORT VISION while speaking with Ms. Graff in July of 2003. Geerhart was able to determine the name of the film and confirm its broadcast on The Ed Sullivan Show by looking it up on an Internet episode guide and confirming its broadcast through contemporaneous newspaper television listings.

[10] “Question of the Week,” Animation Magazine Question of the Week, October 31, 2007.

[11] The copy of A SHORT VISION used for the purposes of researching this article was obtained from the National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland, Record Group 311: Records of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, 1956-2005: 311.80 9. Prior to May 19, 2009, the BFI restricted viewing of A SHORT VISION to persons in the UK with library accounts. CONELRAD salutes the BFI for finally posting this great film on YouTube for all to see!

[12] CONELRAD’s Bill Geerhart was able to view and transcribe Ed Sullivan’s remarks from the May 27, 1956 broadcast through the generosity of Andrew Solt and his company, SOFA Entertainment.

[13] Peter Foldes’ lead creative role in the creation of A SHORT VISION was confirmed through an e-mail interview with his former wife and filmmaking partner, Joan Foldes: E-mail to Bill Geerhart from Joan Foldes, April 28, 2009. The details regarding Foldes birthplace, birth year and education were derived from: Jeff Lenburg, Who’s Who in Animated Cartoon: an international guide to film & television’s award winning and legendary animators (Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2006). Detail of how Peter and Joan Foldes met is from the Tate Britain SHORT VISION screening entry.

[14] Michael Brooke, A SHORT VISION, BFI ScreenOnline entry. Brooke also notes that A SHORT VISION’s composer, Matyas Seiber, worked with John Halas.

[15] “Abstract Paintings,” the London Times, February 5, 1949.

[16] E-mail to Bill Geerhart from Joan Foldes, April 28, 2009.

[17] Ralph Stephenson, The Animated Film (London: Tantivy Press, 1973), p. 109.

[18] Award is cited on the official Cannes Film Festival website under the entries for both Joan and Peter Foldes.

[19] E-mail to Bill Geerhart from Joan Foldes, April 28, 2009.

[20] Roger Manvell, The Living Screen (London: Harrap & Co., Ltd., 1961)

[21] Carol Young, “Shock Wave from A-Bomb Film Rocks Nation’s TV Audience,” New York World-Telegram and Sun (p. 2), May 27, 1956. Detail of when and where Sullivan first saw A SHORT VISION is from Associated Press, “Ed Sullivan’s Shocker Frightens TV Viewers,” the Post-Standard (Syracuse, NY), May 29, 1956.

[22] “Anti-War Cartoon to Repeat on TV,” Hollywood Reporter, May 29, 1956.

[23] Leonard, A Really Big Show, p. 230.

[24] For Sullivan’s evolving Fifties Cold War attitudes see Maguire, Impresario, page 223. For detail on Sullivan’s criticism of Senator Joseph McCarthy for “character assassination,” see Maguire, p. 145. For detail on Sullivan’s Castro interview see Maguire, pp. 215-220. It should be noted that despite Sullivan’s easing of Cold War rhetoric, he apparently still held a grudge against Soviet bears. Per Leonard, A Really Big Show, p. 120, there was an incident on Sullivan’s show in which trained Russian bears performed a bicycling act as planned, but then “went after the audience.” Leonard quotes the host as screaming “Get those goddamned Communist killers out of my theater!”

[25] The cameras were famously focused above Presley’s hips when he performed “Hound Dog” on September 9, 1956: Maguire, Impresario, p. 195; Leonard’s A Really Big Show, p. 39, provides the following accompanying photo text regarding Ms. Mansfield nearly animated appearance: “In the hopes of not shocking the audience at home, frightened producers and stagehands tried to subdue anatomical wonder Jayne Mansfield… Jayne and Ed came up with the idea that she would play the violin.”

[26] “Arthur’s New Art: Former Actor Triumphs in the Short Film Field,” New York Times, January 19, 1958; “Film Maker Sponsor of 38 Prize Pictures,” Los Angeles Times, March 17, 1958.

[27] E-mail to Bill Geerhart from Joan Foldes, April 28, 2009.

[28] George K. Arthur, Columbia University Oral History, pp. 20-21.

[29] E-mail to Bill Geerhart from Joan Foldes, April 28, 2009.

[30] Television listing for The Ed Sullivan Show, the Los Angeles Examiner, May 27, 1956. Other listings that CONELRAD looked at were: “Television Programs,” New York Times, May 27, 1956; Walter Ames, TV column, Los Angeles Times, May 27, 1956; “Today’s Best On TV,” Mansfield, Ohio News-Journal, May 27, 1956; TV Log, Oakland Tribune, May 27, 1956; “Sunday TV Picks,” the Nonpareil (Council Bluffs Iowa), May 27, 1956. All of these listings mentioned some configuration of Sullivan’s guests for that evening, but none mentioned a film.

[31] Associated Press, “B52 Air Drop of H-Bomb Termed Success,” the Albuquerque Tribune, May 21, 1958.

[32] CONELRAD was able to the view the relevant clips from the May 27, 1956 and June 10, 1956 broadcasts of The Ed Sullivan Show thanks to the generosity of Andrew Solt and SOFA Entertainment.

[33] For ratings see Young, “Shock Wave…” and “Anti-War Cartoon to Repeat on TV,” Hollywood Reporter, May 29, 1956. Both articles note that NBC’s rating in the competing timeslot was 7.2.

[34] Young, “Shock Wave…” Young’s quote from the London Times does not appear to be accurate. The London Times has its entire archive online and CONELRAD could find no such quote. The Times did publish a brief review of A SHORT VISION on January 27, 1956. That review is presented verbatim in this article.

[35] Associated Press, “Ed Sullivan A-Film Shocks Viewers,” the Independent (Long Beach, CA), May 29, 1956.

[36] “Anti-War Document (editorial),” the Post-Standard (Syracuse, NY), May 30, 1956.

[37] Walter Ames (column), the Los Angeles Times, May 31, 1956.

[38] Week in Review, Time magazine, June 11, 1956.

[39] E-mail to Bill Geerhart from CBS Audience Services Director Ray Faiola, March 19, 2009.

[40] CONELRAD’s Bill Geerhart confirmed the absence of A SHORT VISION-related material in the Ed Sullivan Papers collection in a telephone conversation with an archivist from the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research at the Wisconsin Historical Society on March 18, 2009

[41] E-mail to Bill Geerhart from James Maguire, March 10, 2009. For a list of all of the biographies on Ed Sullivan see the bibliography. None mention A SHORT VISION.

[42] The Ed Sullivan Show listing, TV Guide, week of June 9-15, 1956. Other sources that mentioned A SHORT VISION’s reprise: Los Angeles Examiner TV listing, June 10, 1956; Walter Ames TV Column, May 31, 1956.

[43] Leonard, A Really Big Show, p. 301. Sullivan’s longest running gossip column, “Little Old New York,” appeared for decades (encompassing and surpassing the host’s television years) in the New York Daily News. Per Maguire, Impresario, p. 301, Sullivan’s last “Little Old New York” column was published the day after his death.

[44] Sullivan’s remark about “requests from civil defense bodies” may help explain how a print of the film wound up at NARA in the FEMA records group (see bibliography). However, per the company that CONELRAD hired to perform the digital transfer from NARA’s copy, there were no paper documents that accompanied the film. CONELRAD has a pending request with NARA to see if there are any documents in their text records related to A SHORT VISION.

[45] CONELRAD was able to the view the relevant clip from the June 10, 1956 broadcast of The Ed Sullivan Show thanks to the generosity of Andrew Solt and SOFA Entertainment.

[46] “Marlo Lewis is Dead; TV Producer Was 77,” the New York Times, June 10, 1993.

[47] Telephone interview with Marlo Lewis, Jr. conducted by Bill Geerhart, March 27, 2009.

[48] Evidence of A SHORT VISION’s theatrical release can be found in newspaper theater advertisements as published in the North Adams (Massachusetts) Transcript, August 30, 1956 and the Berkshire Massachusetts) Eagle, September 1, 1956. The review quote is from Howard Thompson, “Newcomers in 16mm,” the New York Times, October 21, 1956. Also: “Of Local Origin,” New York Times, June 30, 1956 mentions A SHORT VISION’s distribution by Brandon Films, Inc. The Saturday Review (“Ideas on Film,” July 6, 1957) published a capsule review calling A SHORT VISION “a sobering film in animation.” This capsule review also notes that A SHORT VISION was among the “top” 23 films that played at the Golden Reel Film Festival in New York City in June of 1957.

[49] “A Short Vision,” review, The Monthly Film Bulletin (published by the British Film Institute), volume 23, no. 270, July 1956, p 95. It is interesting to note that the reviewer does not disclose the BFI’s involvement in the production of the film. The British print of the film which can now be seen on YouTube includes the following credit: “completed with the support of the British Film Institute’s Experimental Film Fund.”

[50] The UCLA Film and Television Archive has an Encyclopedia Britannica print of A SHORT VISION. The copy obtained by CONELRAD from the National Archives has no company listed, just the credit “George K. Arthur Presents…”

[51] A SHORT VISION’s September 1956 Venice Film Festival prize for Premio per il miglior sperimentale (prize for best experimental film) was confirmed via e-mail on March 12, 2009 by Michele Mangione, ASAC Media Library Curator for La Niennale di Venezia.

[52] A May 24, 2009 search for A SHORT VISION on IMdB and Wikipedia found no entry for the film.

[53] Peter Foldes’ post-A SHORT VISION biographical material was derived, in part, from Lenberg, Who’s Who in Animated Cartoon, pp. 91-92. Lenburg cites A LAD AND HIS FUTURE as being Foldes first French film in 1956, but based on the London Times article “Wide Range in Mood and Style at Festival of Short Films,” June 29, 1965 and the IMdB entry for this film, its year of release was 1965, not 1956. Per IMdB’s entry for the 1975 Academy Awards, HUNGER lost to CLOSED ON MONDAYS (1974) by Will Vinton and Bob Gardiner. The London Times reviewed one of Peter Foldes’ Sixties art exhibits in “Narrative Painting of Today,” June 14, 1963. The unnamed reviewer said, in part, that Foldes work “gives a personal version of the way in which the narrative element may be reintroduced into pictorial art, not by returning to nineteenth-century methods but by pooling ideas and devices of more recent times.”

[54] Cesar Award information and date of death derived from the IMdB entry on Peter Foldes. Date of death confirmed as March 29, 1977 in Jeff Lenburg, Who’s Who in Animated Cartoon, p. 91.

[55] Charles Champlin, “Prize Winners,” Albuquerque Journal, June 2, 1977.

[56] Relatives of Joan Foldes advised CONELRAD’s Bill Geerhart of the Foldes’ divorce and Joan’s remarriage and current home city. The detail of Joan’s poetry writing was derived from Tate Britain SHORT VISION screening entry

[57] Death dates for Arthur, McKetchnie, Seiber derived from their respective IMdB entries.

[58] “Ed Sullivan is Dead at 73; Charmed Millions on TV,” the New York Times, October 14, 1974. Details on Sullivan’s post-1971 activities derived from Maguire, Impresario, pp. 295-301.