“All FBI offices, day-to-day and emergency, should be supplied in advance and on a secret basis, with the location of the Congressional relocation site and with instructions that in the event of a Presidential proclamation calling upon the Congress to convene at the Congressional relocation site, the FBI should inform members of Congress so presenting themselves and so establishing their identity, of the location of the Congressional relocation site.”

- Text from a February 10, 1961 FBI memo recommending the protocol for notifying members of the United States Congress of their emergency relocation site

Thanks to investigative journalist Ted Gup we all know that the super bunker at the Greenbrier resort in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia was intended for use by the Congress in the event of a nuclear attack on the United States. He revealed its unlikely existence on May 31, 1992 in a Washington Post magazine cover story. Not included in Mr. Gup’s very detailed exposé is the procedure by which rank and file members of Congress would have been made aware of the bunker. This post will fill in that small gap in the Greenbrier bunker knowledge base.

Earlier in the year we published a post about government correspondence concerning the sensitive task of notifying members of Congress of their top secret relocation site in the event of a national emergency during the Cold War.[1] The author of the document that we presented in our previous story suggested several options to his addressee on how to handle this apocalyptic chore. One possibility included saddling the Federal Bureau of Investigation with the notification duty. The reasoning behind this particular choice was the concern that the security of the site might eventually be compromised if an ever increasing number of active and former Congressmen had ongoing knowledge of its location. Obviously, nothing was ruled in or ruled out in this one-sided memo, so we (and our readers) were left hanging awaiting another memo that revealed the decision. By virtue of the tireless FOIA filing efforts of GovernmentAttic.org we now have the additional documents that prove that the Greenbrier bunker notification responsibility was, in fact, assigned to the FBI. And, surprisingly, it was not a job that was immediately accepted with open arms by the Bureau.

Indeed, in assessing the White House’s request for this assistance, senior FBI agent Alan H. Belmont argued against it. In an October 21, 1957 internal memo Belmont was more concerned with the bureau’s mission of “rounding up enemy aliens” during a crisis – not helping panicky legislators learn about their shelter accommodations. Belmont also raised the possibility of “some member of Congress” coming to a FBI field office to demand the location of the bunker site prior to the approved disclosure period (i.e. after a Presidential proclamation). He concluded that this scenario would put the “Bureau in a bad light” and imply “that the White House does not sufficiently trust the rank and file of the Congress” with the information.

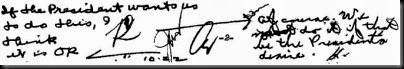

But FBI leadership quickly disregarded these concerns in the form of terse mark-ups to Belmont’s correspondence. Associate Director Clyde Tolson weighed in first by scribbling “If the President wants us to do this, I think it is OK – T.” Director J. Edgar Hoover concurred and wrote the following next to Tolson’s note: “Of course. We must do it if that is the President’s desire. H.”

That settled that. And then there was a period of silence while the Greenbrier bunker was actually built. In early 1961, as the bunker was nearing operational status, the issue of congressional notification was revisited in more concrete terms.

Following some bureaucratic revisions, a protocol for the secret notification duty was arrived at between the FBI and the Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization (OCDM). According to an internal FBI memo, the Attorney General was officially notified of the agency’s new responsibility via a letter dated February 14, 1961.

In a March 7, 1961 memo Director Hoover stated that FBI field offices “have been advised of the Bureau’s responsibility in informing Members of Congress, upon their request, as to the specific location of the Congressional relocation site. This information will only be made available to Congressmen in the event of an emergency, when, in the judgment of the President, Congress should convene outside Washington, D.C. The identity of the Congressional relocation site is being maintained by our field offices in sealed envelopes, to be opened only upon the issuance of the Presidential proclamation.”

Hoover’s memo to the field offices—distributed through the Albany, New York office—provided additional details regarding the procedure:

“Attached hereto, for each office, is an appropriate number of sealed envelopes, classified Secret, each containing the identity of the specific location of the Congressional relocation site. In accordance with Congressional instructions received through OCDM, these envelopes should not be opened, except in the event the condition cited previously exists. A sealed envelope should be filed in each copy of your office defense plan as Appendix 25…”

One last bit of business that needed to be addressed was where exactly to store the defense plan containing the location of the Congressional relocation site at the Records Branch of the FBI in Washington, DC. In a memo dated March 14, 1961, Mr. Belmont helpfully suggested that “Bureau File 66-17388” be retained in the Confidential File Room. In 1964 the matter was revisited in the form of a memo requesting confirmation that the file still needed to reside in what was now called the “Special File Room.” Per the initials of the responsible supervisors, the secret location of the Greenbrier bunker stayed put in its super secure haven.[2]

But where were the field offices maintaining their copies of the defense plans and sealed envelopes (aka Appendix 25) and were they secure? Sixteen years after the first envelope was licked, someone finally asked. According to a March 8, 1977 memo, representatives of the Defense Preparedness Agency (a successor agency to OCDM) “wanted reassurance that these sealed envelopes are kept in a safe place and had not been tampered with in any way…” This same memo contained FBI Director Clarence M. Kelley’s request to “All SACS” that each of them confirm “the safe location and integrity of sealed envelopes” and notify FBI headquarters of the results of their inspection by close of business on March 11, 1977.

Miraculously, most of the field offices had nothing but good news to report back to the Director. A sampling of these routine replies can be viewed here. There was one case in Chicago where one of the sealed envelopes had been “worn on one end and had been sealed with Scotch tape, dated and initialed.” There were a few other anomalies with regard to the envelopes in other offices, but these issues were reported and did not set off any alarm bells. And then there was the case of the Butte, Montana field office.

The Butte office, reputedly a dumping ground for the worst FBI agents in the Bureau,[3] responded to headquarters in a memo that stated that the “envelope must have been inadvertently destroyed when all secret material [was] ground up” when they updated their plans the previous year. They then meekly requested a replacement envelope. The Director was having none of it. He fired back a memo rebutting their shredder excuse and demanded that an “exhaustive search” be conducted with a subsequent report of their efforts. Unfortunately, there is no follow-up memo included in the declassified documents.

Presumably the Butte office received their replacement envelope (and a reprimand) and maintained its integrity until the office was permanently closed in 1989.

There is no evidence contained in the declassified documents released thus far that the FBI was relieved of its notification responsibilities prior to Ted Gup’s published revelation of the existence of the Greenbrier bunker in 1992. It is therefore assumed that the procedure remained in place for the life of the bunker.

Have the field offices been assigned a similar notification task in the years since the decommissioning of the Greenbrier bunker? If there is a new Congressional relocation site, the answer to this question may be yes. After all, the level of trust between the White House and Congress has only declined since 1961.

REFERENCES

Unless otherwise noted, all of the documents referenced in this post have been excerpted from the following FOIA release:

"Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) war/emergency plans and Bureau assistance for members of Congress in the event of war/emergency, 1955-1977"

Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation

Attn: FOI/PA Request

Record/Information Dissemination Section

170 Marcel Drive

Winchester, VA 22602-4843

To read all of the memos referenced in this post, please see our FBI Congressional Relocation Site Correspondence collection on Scribd.

[1] The redacted government documents referenced in this post do not mention the Greenbrier resort bunker in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia as the relocation site for the U.S. Congress, but another declassified FBI document we have posted does. See: http://www.scribd.com/doc/102562220/Greenbrier-FBI-Memos-1957.

[2] CONELRAD has filed a Freedom of Information request with the FBI for Bureau File 66-17388 including Appendix 25 with a special note that we would like the contents of the sealed envelope photocopied. We will update this post if and when we receive this documentation.

[3] For a mention of the Butte field office’s bad reputation see page 28 of “From Appalachia to the White House: My Life in the Secret Service” by Joe Dye [Bloomington, IN: CrossBooks, 2011]. See also pages 67, 216 and 396 of “The FBI” by Ronald Kessler [New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994] in which he references the history of the notorious field office.