“There was a job to be done and like many others I tried to help. I thought Ron was the ideal man to do the speech.”

John B. Kilroy to CONELRAD[1]

INTRODUCTION

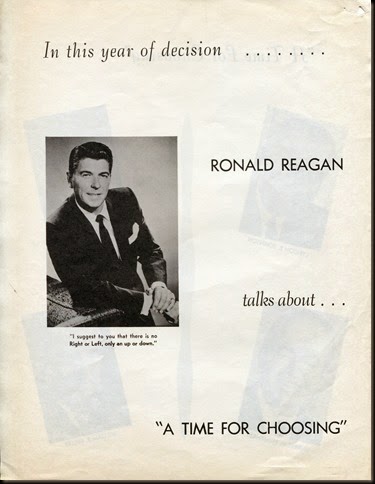

To many conservatives young and old Ronald Reagan’s October 27, 1964 televised address A Time for Choosing is the moment that the modern incarnation of their movement was born. Over the course of fifty years “The Speech,” as it has been dubbed, has spawned its own mythology in books, articles, documentaries and even a made-for-TV movie. Indeed, the story of citizen Reagan’s nationally broadcast star turn on behalf of doomed GOP nominee Senator Barry Goldwater has become a hallowed chapter in the late president’s biography. And yet, even after half a century, precious few details of how the speech was produced and put on the air have ever been published. This excerpt, derived from a much longer examination of the speech, seeks to address these information gaps and recognize the unsung men who made Reagan’s historic political debut possible. A more exhaustive history of A Time for Choosing will be posted here in the near future.

“SURE, IF YOU THINK IT WOULD DO ANY GOOD”

Most Reagan biographies cite a more or less identical confluence of events that resulted in the future president’s appearing on national television on October 27, 1964. Ronald Reagan himself confirms most of the oft-repeated chronology in his 1990 autobiography, An American Life. The catalyst for his speech being selected for national exposure was, as Reagan recounts in his book, a $1,000-a-plate fundraising dinner for “about 800 Republicans” at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles during the “late summer.”[2] According to two contemporaneous articles from the Los Angeles Times, the pricey fundraiser occurred on October 1, 1964 and it accommodated between 400 and 500 guests.[3] Reagan was to be the star attraction of the evening while Goldwater, who was campaigning elsewhere, was scheduled to address the crowd briefly on film.[4]

Author Curtis Patrick, who at the time was a young advance man and personal assistant to Senator Goldwater, attended the event and discusses it in his book Reagan: What Was He Really Like? Volume 1.[5] Patrick told CONELRAD in an interview that he escorted the candidate’s wife to the venue. When asked how many people might have been at the club, he replied: "My memory of the Cocoanut Grove is [that it was] small and so I would say 500 might be more accurate." As for the speech itself, Patrick remembered it vividly perhaps because it was the first time he had ever seen the actor speak live and in person. He recalled that when Reagan had finished that night’s iteration of The Speech, “Mrs. Goldwater turned to me and asked me 'what did you think?' I said [it was] stunning.”[6]

Reagan, at the time, was the statewide co-chairman of Citizens for Goldwater-Miller and his duties consisted primarily of touring California making speeches supporting the ticket.[7] This event was, for all practical purposes, just another night on the circuit for him.

Among the well-heeled donors in attendance that evening was a group of influential California millionaires and powerbrokers who were bowled over by the fading film and TV star’s stirring Cold War oratory. Reagan doesn’t name names in his book, but various other accounts have claimed that oil company magnate Henry Salvatori and automobile sales king Holmes Tuttle were at the function. And since they were the two people who organized the dinner it would make sense that they were present. According to Reagan, after the dinner he was asked by five or six people to join them at their table at the now “almost empty” Cocoanut Grove. These people, whom Reagan writes he later learned included major state GOP donors, asked him if he would be willing to film his speech for television. “Sure,” the Gipper replied, “if you think it would do any good.”[8]

So how did an informal agreement at an L.A. nightclub evolve into a polished, independently funded network TV special in a matter of weeks? Based on CONELRAD’s extensive research on the history of A Time for Choosing, a small team of California Republicans led by a driven, self-made businessman made it all happen.

KILROY WAS THERE

Despite the fact that Southern California real estate developer John B. Kilroy speaks at the end of Reagan’s famous October 27, 1964 taped television broadcast, his name is not commonly linked to A Time for Choosing.

There are a few magazine and newspaper articles from the mid-1960s that directly credit Kilroy (and TV producer Robert B. Raisbeck) for the production of the broadcast, but the only book that mentions him (aside from Kilroy’s own 2012 autobiography) as having anything to do with the speech is Kurt Schuparra’s Triumph of the Right: The Rise of the California Movement, 1945-1966. However, Schuparra relegates Kilroy to a somewhat skeptical endnote that cites an oral history interview of prominent California Republican Gardiner Johnson who was active in the ’64 Goldwater campaign. Johnson’s belief in Kilroy’s key part in A Time for Choosing is quite a bit stronger than Schuparra’s.[9] Johnson, it turns out, was right but he was nearly alone in his conviction.

Kilroy, who clearly prefers yacht racing to defending his own political accomplishments, was perhaps the person most responsible for getting Ronald Reagan on the air on October 27, 1964. The staunchly anti-communist businessman’s role in what Reagan would later call “one of the most important milestones of my life” began when a friend made him aware of the speech.[10] Reagan had been giving variations of “The Speech” for years beginning in the 1950s when he began touring the country as a corporate goodwill ambassador for General Electric. He, of course, also hosted G.E. Theater on television from 1954 to 1962.[11]

In an interview with CONELRAD in 2011 Kilroy, who was then 88-years-old and extremely lucid, told us, “[Robert B.] Raisbeck had heard it and recommended that I hear it,” adding that Raisbeck may have had an audio tape of the speech. Kilroy confirmed in his interview that he was not at the Cocoanut Grove on October 1st. However, both he and Raisbeck knew Henry Salvatori.[12] In any case, Kilroy said that hearing Reagan speak out on the issues was one of the sparks that inspired him and his team to want to adapt the speech for television.[13]

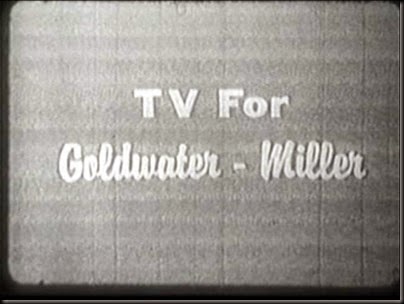

According to Kilroy’s book, Kialoa US-1: Dare to Win in Business, in Sailing, in Life, his next move after confirming Reagan’s willingness to participate on the project, was to fly to Washington, D.C. and meet with Dean Burch, the new chairman of the Republican National Committee, and Ralph Cordiner, the RNC finance chairman (and Reagan’s former boss at G.E.). With their agreement on the plan to put Reagan’s speech on television, a new committee was launched called “TV for Goldwater-Miller” with Kilroy as national chairman.[14]

On September 14, 1964 Kilroy and committee co-chairman, Schick Safety Razor company owner Patrick J. Frawley, Jr. (who later helped sponsor Up with People!), sent out a fundraising letter declaring their overarching goal for the campaign:

“The principle obstacle to his [Goldwater’s] election is the tremendous distortion of his message by all communications media. To offset this, we must keep Barry Goldwater on television constantly between now and November 3rd…”[15]

TV for Goldwater Fundraising Letter

THE TEAM

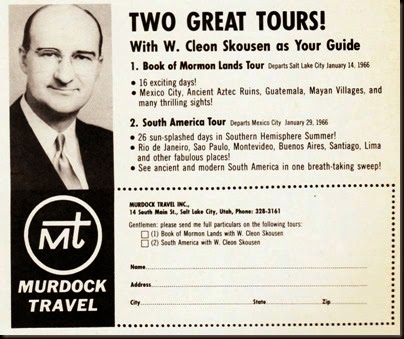

Kilroy explained to CONELRAD that he first met the creative team that would produce Reagan’s A Time for Choosing well before the Goldwater presidential campaign. In fact, Kilroy said that they had become acquainted with one another through their affiliation with the controversial anti-communist activist W. Cleon Skousen.[16] Skousen, a former FBI agent and future muse to radio and television personality Glenn Beck, also had public ties to Reagan.[17] Both Skousen and Reagan had made joint appearances at rallies for Fred Schwarz’s Christian Anti-Communism Crusade (CACC) in the early 1960s.[18]

In addition to Kilroy, the team included the previously mentioned producer and advertising man Robert B. Raisbeck, Jr. and veteran television and radio director Robert “Doc” Livingston.[19]

Raisbeck’s surviving son, Peter Raisbeck, confirmed to CONELRAD that it was Kilroy who recruited the team to work for Goldwater and Reagan and that his father would occasionally reminisce with the family about his work on A Time for Choosing. The younger Raisbeck also confirmed his father’s association with Skousen: “Dad did know and work with Cleon Skousen on his anti-communist activities for several years.”

Robert “Doc” Livingston, who died in 2003, left no survivors that we know of.[20] We were, however, able to find a colleague of Livingston’s from his long tenure as a staff director at KNBC in Los Angeles. The Reverend Doctor Thandeka (formerly known as Sue Booker) was a writer and producer at the station and worked frequently with Livingston in the 1970s and ‘80s. When asked if she was aware of his role in A Time for Choosing or his political leanings, Thandeka expressed surprise: “I always assumed he was liberal, but we never talked about politics, just show business.” Since we could find no photographs of Livingston, we asked Thandeka to describe him. Without missing a beat, she said “Like Will Geer, but taller and thinner.” She added that he was like a “favorite uncle” who “always smiled” and who was not “easily ruffled.”[21]

Long before the ’64 campaign Raisbeck and Livingston collaborated on the early local TV program Television Talent Time in Los Angeles.[22]

SEED MONEY, PRODUCTION AND LOCAL BROADCASTS

According to Kilroy, Henry Salvatori, the co-organizer of the Cocoanut Grove fundraiser, became a “50/50” partner with him in providing the “seed money” to produce A Time for Choosing and get it on the air locally. When asked where the speech was taped, he told CONELRAD: “At one of the one of the Los Angeles studios…where all the facilities are there – the lighting, etcetera.”[23]

CONELRAD reached out to R. Duke Blackwood, the Executive Director of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library about the particulars of the venue and the date of the taping of A Time for Choosing. He conveyed to us that the person who has custody of the original videotape states that the recording date was October 12, 1964 from 10:15 to 10:45 (whether AM or PM was unknown by the source) and that the site of the taping was a television studio at NBC in Burbank, California.[24] This date conforms to the tentative shooting schedule mentioned in an October 5, 1964 advertising agency memo: “Mr. Raisbeck plans to film a half-hour Ronald Reagan speech on or about October 10.” The memo also mentions that the Reagan film and another TV Committee project were “out of the agency’s purlieu [sic]” or purview.[25]

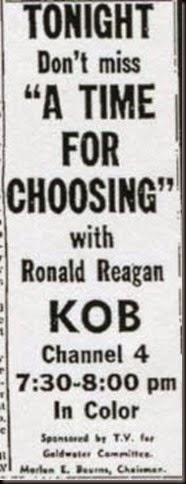

The speech was videotaped using RCA color cameras, but the version that the Reagan Foundation features on their YouTube channel (and supplied by the Reagan Library) is a black and white kinescope. Per Mr. Blackwood, the Reagan Library recently found what they thought was an original color copy of the tape, but someone had taped over it. The Library is still trying to obtain a color version of the speech.[26] There is, incidentally, some evidence that A Time for Choosing was broadcast in color in 1964. An October 27, 1964 Albuquerque Journal newspaper ad promotes the speech as being “In Color.” Of course, this could also just be a mistake.[27]

After the taping was completed, Kilroy told us that he and a couple others worked on editing it because their star had gone long by a few minutes.[28] There is just one obvious edit in the tape and it occurs near the end of the speech exactly as Reagan concludes his famous “thousand years of darkness” line.[29]

The finished product was not your average “TV talker” featuring a bland politician reciting a stump speech into a static camera in an empty room. From the first overhead camera shot slowly tracking in on Reagan speaking at the podium in the studio dressed to look like a rally hall, the viewer knows that this is going to be different. By most accounts, including his own, Reagan insisted on bringing in an audience and it was this decision that made all the difference.[30] The enthusiastic reaction shots of a mostly youthful audience packed with Goldwater Girls provide what appears to be a palpable energy to the speaker. By the time Reagan wraps up his address to a standing ovation, it is clear that the definitive version of “The Speech” has just been delivered.

Kilroy’s next task was to get Ronald and Nancy Reagan’s approval of his cut of the tape. The Reagans, according to Kilroy, were initially against the campaign contribution plea at the end of the broadcast. “The money pitch was a hard thing to do,” he told us. “Ron and Nancy didn’t like it, so we convinced them. Nancy was the hardest to convince.”[31] The reluctance on the part of the Reagans to solicit donations may seem quaint in today’s world of billion dollar presidential campaigns, but in 1964 fundraising from televised political ads was unprecedented.[32] And it was an innovation that did not always sit well with Goldwater’s high command. Campaign manager Denison Kitchel vetoed an appended appeal for donations at the end of the stolid half-hour campaign film Conversations at Gettysburg that featured Goldwater talking to former President Dwight D. Eisenhower on his Pennsylvania farm. Kitchel was concerned about cheapening the dignity of the presidency when he should have been worried about producing a boring advertisement.[33]

Kilroy told CONELRAD that A Time for Choosing was broadcast in local markets around California “several times” before its nationwide network debut.[34] CONELRAD was only able to find one example of a local broadcast: October 23, 1964 on KNBC in the Los Angeles market. It was advertised in local newspapers without a title, but with the promotional line of “Ronald Reagan speaking out on the important issues of this campaign.”[35] Kilroy recalled that “the response was tremendous wherever it played.”[36] According to the campaign’s advertising agency documents reviewed by CONELRAD, the network time for the October 27th airing of the speech was purchased on October 22nd - the day before the local broadcast of the speech.[37] Therefore, the money used to buy the network time must have come from appeals for donations from other TV for Goldwater-Miller Committee programs such as the “Captive Nations Rally telethon” that aired on October 18th[38]

A claim that has been made in at least two books holds that a group called “Brothers for Goldwater” of Greenwich, Connecticut chaired by movie star John Wayne contributed the funds necessary to get Reagan on the air in 1964.[39] The story, the source of which is a 1984 letter from former General Electric employee J.J. Wuerthner, Jr. to Michael Deaver at the White House, is that the Brothers presented Goldwater with a check for $60,000 at his Madison Square Garden rally on October 20, 1964. Wuerthner goes on to state in his letter that his G.E. boss, Lemuel Boulware, asked Goldwater to “earmark the money for a nationwide Reagan radio and TV broadcast on October 27th.”[40] There are three problems with this claim: 1.) The Goldwater rally was held on October 26, 1964, not October 20th. 2.) The airtime was bought from NBC on October 22nd – before the Madison Square Garden rally and 3.) A report on 1964 campaign spending published by Congressional Quarterly reflects that the total receipts and expenditures for the Brothers group during the period of September 1, 1964 through December 31, 1964 was only $26,317.[41]

Could some of that money have found its way into the collection plate for Reagan’s airtime? Maybe, but even if all of it was used for the Reagan speech it would have covered little more than the “preemption” fee charged by the network (see next section). The likelier explanation, and one supported by the contemporaneous advertising agency documents, is that the funding came from the contributions brought in by the televised appeals.

MAD MEN

According to the records of the Republican National Committee’s official advertising agency, Erwin Wasey, Ruthrauff & Ryan (EWR & R), not everyone was thrilled with the idea of using network time during the closing week of the campaign to feature someone other than the candidate. EWR & R’s account executive for the RNC, Albert Tilt, noted in his October 23rd meeting summary that such a plan was “strategic suicide” and that the agency “strongly protested the use of these funds at the expense of a last week of spots.”[42] The agency produced spots to which Tilt refers include one in which Goldwater defends himself against being labeled as “imprudent and impulsive.” In another, the candidate answers a tea-sipping housewife’s concerns about communism. And there was even a twenty second version of Conversation at Gettysburg featuring Eisenhower saying the word “tommyrot.”[43]

How much money did it cost to put Ronald Reagan in prime time on NBC for a half hour in 1964? According to Tilt’s memo, the final charge was $115,236 which included a “preemption” charge of $22,300 presumably for knocking David Frost’s That Was the Week That Was off the air for another week.[44]

On October 25th, campaign manager Denison Kitchel and self-appointed guru William Baroody tried to have A Time for Choosing withdrawn from the network schedule and replaced by an agency produced Goldwater program. Accounts of this showdown have been published in slightly altered versions many times before, but Kitchel and Baroody ostensibly objected to a passage in the speech about Social Security and prevailed upon Goldwater to call Reagan in order to have the speech pulled. Reagan first asked Goldwater if he had heard the program and then explained to him that the time was not his to give up. The end result, according to most versions of this tug of war, was that Goldwater heard the audio of the speech and asked his advisers “What the hell’s wrong with that?” The decision to proceed had apparently been made by the candidate himself.[45]

But Kitchel and Baroody would not give up so easily. In his inside account of the 1964 election, A Glorious Disaster, campaign treasurer J. William Middendorf II reveals that the duo was trying to “substitute a Goldwater re-run” three hours before the Reagan broadcast was set to air.[46] Kilroy backed up Middendorf’s recollection and told CONELRAD that TV for Goldwater-Miller was a separate entity from the campaign advertising arm and he was resolved not to surrender the air time that had been purchased specifically for Reagan. “We weren’t in the business to finance a Barry speech,” an emphatic Kilroy told us. “Our responsibility was to Reagan. We told them no. I told Dean Burch that if Goldwater doesn’t want the speech to run to call me. Barry liked the speech. The problem was with his advisers.”[47]

In his book Middendorf speculates that Kitchel and Baroody may have been “goaded” by EWR & R to take action because the agency stood to lose a significant amount of commission money on the airing of the independently produced and sponsored Reagan speech. Middendorf recounts in his memoir that he had already heard the agency’s complaints directly.[48]

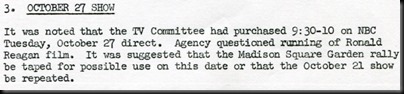

EWR & R’s meeting summary memos written by the aforementioned Albert Tilt provide a fascinating window into the efforts to diminish and then outright replace A Time for Choosing. The following are excerpts from the memos that deal directly with A Time for Choosing.

October 19, 1964 EWR & R Report # 42 to the RNC:

Ronald Reagan Speech – This would appear useful only in its full length as a half-hour for local use.

October 22, 1964 EWR & R Report # 45 to the RNC:

It was noted that the TV Committee had purchased 9:30-10 on NBC Tuesday, October 27 direct. Agency questioned running of Ronald Reagan film. It was suggested that the Madison Square Garden rally be taped for possible use on this date or that the October 21 show be repeated.

October 24 & 25, 1964 EWR & R Report # 47 to the RNC:

Agency was asked to set up a screening of “Brunch with Barry” as a possible re-run for October 27 half-hour purchased by the TV Committee.

It should be noted that Tilt’s summary memos repeatedly mention the TV Committee and their representative, Robert Raisbeck, beginning with the September 3, 1964 issuance. In fact, Raisbeck and the TV Committee, headed by Kilroy, are the only entities referenced in connection to the Reagan program. [49]

SHOWTIME: RONALD REAGAN VERSUS MIA FARROW

At exactly 9:30 p.m. on Tuesday, October 27, 1964 voice actor Art Gilmore introduced A Time for Choosing and launched Ronald Reagan into history.[50] The speech ran against ABC’s hugely popular nighttime soap opera featuring Mia Farrow, Peyton Place, and CBS’s rural sitcom Petticoat Junction. Ironically, this pivotal and triumphant moment in Reagan’s political evolution came in dead last in the ratings. It earned an 18.0 share of the audience in the Arbitron rankings compared to Peyton Place which won the time period with a 42.0 share.[51]

But based on the reaction at Republican field offices, RNC headquarters and Western Union, the core Republican audience that night was watching Reagan, not Farrow.[52] Lucille Boston, who was in charge of the Westwood Goldwater for President Headquarters (in Los Angeles) and who was a personal assistant to Reagan for a period during the campaign, told CONELRAD in an email:

What I remember the most vividly was that just after the speech, the phone board in the headquarters lit up like Times Square and we could not handle all the calls coming in. All said, “Reagan is fabulous. We need to have him run for office.” The people were ecstatic and there is no question but that the speech propelled Reagan into the forefront.[53]

F. Clifton White, the architect of the Draft Goldwater movement and the Director of Citizens for Goldwater-Miller, sent Reagan a telegram from RNC headquarters the following day congratulating him on the telecast and noting that the “phones are ringing off the hook here.” White was just one of hundreds of people who shared their sentiments about the speech via telegram, letter or phone call. The legendary film director John Ford was another: “GREAT RONNIE GREAT,” was the succinct review he transmitted from Honolulu. And Wilma Batz of Peoria, Illinois asked Reagan via telegram: “I know you’re an actor, but are you running for president?” The Reagan Library has a comparatively small sampling of the telegrams some of which can be viewed here. The Dean Burch Papers at Arizona State University in Tempe contain a much larger cache of fan mail which CONELRAD has perused.[54]

Many of these communications from the public and regional Republican officials begged for a re-run of A Time for Choosing.[55] They got their wish on Halloween when the speech was broadcast nationally for a second time on NBC in prime time. It was paired with a separate half-hour campaign plea for Goldwater starring John Wayne entitled A Time for Courage.[56] The Reagan speech went on to be run repeatedly on local television stations.[57]

P.O. BOX 80: FOLLOW THE MONEY

Of course, in addition to the letters and telegrams praising Reagan’s speech, checks came pouring into berry king Walter Knott’s P.O. Box 80 at the Terminal Annex Post Office in downtown Los Angeles. Kilroy confirmed to CONELRAD that the P.O. Box screen seen at the end of A Time for Choosing belonged to Knott, an arch conservative who was also chairman of the Citizens for Goldwater-Miller Committee of Orange County.[58]

The donations were processed by Security First National Bank which charged a fifty cent fee per contribution to provide a “Thank You” note to each contributor and to provide financial reporting to the Congressional Oversight Group, the Republican Party and the TV for Goldwater-Miller Committee.[59]

In the many campaign memoirs and autobiographies that have been published since 1964, there have been a wide variety of claims concerning how much money Reagan raised with his televised speech. Reagan’s own figure in his 1990 book may be the highest estimate at $8 million. On the lower end of the spectrum, Stephen Hess and David S. Broder guessed $600,000 in their 1968 book The Republican Establishment.[60]

Congressional Quarterly published the most extensive accounting of 1964 campaign finances in a special report published in their January 21, 1966 issue. According to CQ, during the last six days of the campaign—the period that Reagan’s speech would have had its biggest impact among contributors—a total of $2,800,000 was raised. But this figure includes all campaign appeals not just Reagan’s. However, CQ singled out Reagan’s “direct television appeal” (a.k.a. A Time for Choosing) and appeals by actor Raymond Massey and RNC head Dean Burch in their tabulation. CQ also reported that “at the end of the calendar year 1964, with all but a few campaign debts paid, the Republican National Committee had a surplus of $314,000; Citizens for Goldwater-Miller $309,006; and the National TV Committee for Goldwater-Miller $506,534.”[61]

CONCLUSION

The internecine bickering over the unused GOP funds and the bitter debates over the party’s future in the wake of Goldwater’s staggering loss to President Lyndon Johnson was still playing out as Ronald Reagan announced his candidacy for governor of California on January 4, 1966.[62] Reagan’s long, occasionally bumpy ascent to the White House was officially underway. And with his election to the presidency in 1980, A Time for Choosing became an even more important event in his life and career. Had he lost, of course, the title of the speech would by now be the answer to a particularly difficult trivia question. But because Reagan was victorious, the then sixteen-year-old broadcast was prominently mentioned in Time magazine’s Man of the Year issue and other effusive profiles on the new President-elect.[63] And it is because Ronald Reagan eventually became president of the United States that the 1964 election will forever be remembered for two remarkable television advertising events, not just one.

POSTSCRIPT

John B. Kilroy, who once memorably described himself to Newsweek magazine as a “damned capitalist,” retired from his company, Kilroy Realty Corp. at the age of 90 in 2013. He had started the companies that ultimately became Kilroy Realty in 1947.[64] The former surfer and all-around modern Renaissance man is currently enjoying life with his wife Nelly and tending to his various philanthropic missions. You can watch a series of biographical videos of Kilroy here, but don’t expect to hear him talk about A Time for Choosing. He’s moved on.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Blumenthal, Sidney. The Rise of the Counter-Establishment: The Conservative Ascent to Political Power. New York: Times Books, 1986.

Boyarsky, Bill. The Rise of Ronald Reagan. New York: Random House, 1968.

Buckley Jr., William F. Flying High: Remembering Barry Goldwater. New York: Basic Books, 2008.

Cannon, Lou. Ronnie and Jesse: A Political Odyssey. New York: Doubleday, 1969.

Cannon, Lou. Reagan. New York: Putnam, 1982.

Cannon, Lou. Governor Reagan: His Rise to Power. New York: Public Affairs, 2003.

Colacello, Bob. Ronnie and Nancy: Their Path to the White House, 1911 to 1980. New York: Warner Books, 2004.

Dallek, Matthew. The Right Movement: Ronald Reagan’s First Victory and the Decisive Turning Point in American Politics. New York: Free Press, 2000.

Davis, Patti. The Way I See It: An Autobiography. New York: Putnam, 1992.

Darman, Jonathan. Landslide: LBJ and Ronald Reagan at the Dawn of a New America. New York: Random House, 2014.

Edgington, Steven D., and Lawrence Brooks De Graaf. The "Kitchen Cabinet": four California citizen advisers of Ronald Reagan : Interviews. [Fullerton]: Oral History Program, California State University, Fullerton, 1983.

Edwards, Anne. Early Reagan. New York: Morrow, 1987.

Edwards, Lee. Goldwater: The Man Who Made a Revolution. Washinton, D.C.: Regnery, 1995.

Eliot, Marc. Reagan: The Hollywood Years. New York: Harmony Books, 2008.

Evans, Thomas W. The Education of Ronald Reagan: The General Electric Years and the Untold Story of His Conversion to Conservatism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2006.

Goldwater, Barry with Jack Casserly. Goldwater. New York: Doubleday, 1988.

Hess, Stephen and David S. Broder. The Republican Establishment. New York: Harper and Row, 1967.

Hoplin, Nicole and Ron Robinson. Funding Fathers: The Unsung Heroes of the Conservative Movement. Washington, D.C.: Regnery, 2008.

Jamieson, Kathleen Hall. Packaging the Presidency: A History and Criticism of Presidential Campaign Advertising. Second Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Kelley, Kitty. Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991.

Kilroy, Jim. Kialoa US-1: Dare to Win : In Business, In Sailing, In Life. [S.l.]: Smith Kerr Assoc., 2012

McGirr, Lisa. Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Right. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002.

Middendorf II, J. William. A Glorious Disaster: Barry Goldwater’s Campaign and the Origins of the Conservative Movement. New York: Basic Books, 2006.

Morrell, Margot. Reagan’s Journey: Lessons from a Remarkable Career. New York: Threshold Editions, 2011.

Morris, Edmund. Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan. New York: Random House, 1999.

Nofziger, Lyn. Nofziger. Washington, D.C.: Regnery, 1992.

Patrick, Curtis. Reagan: What Was He Really Like? Volume 1 (ebook edition). New York: Morgan James Publishing, 2011.

Perlstein, Rick. Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus. New York: Hill and Wang, 2001.

Reagan, Nancy with William Novak. My Turn: The Memoirs of Nancy Reagan. New York: Random House, 1989.

Reagan, Ronald and Richard G. Hubler. Where’s the Rest of Me? The Ronald Reagan Story. New York: Van Rees Press, 1965.

Reagan, Ronald. Speaking My Mind: Selected Speeches. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989.

Reagan, Ronald. An American Life. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990.

Reagan, Ronald, Kiron K. Skinner, Annelise Graebner Anderson, and Martin Anderson. Reagan: A Life in Letters. New York: Free Press, 2003.

Reagan, Ronald, and Douglas Brinkley. The notes: Ronald Reagan's private collection of stories and wisdom. New York: Harper, 2011.

Ritter, Kurt W. and David Henry. Ronald Reagan: The Great Communicator. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1992.

Schoenwald, Jonathan M. A time for choosing: the rise of modern american conservatism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Schuparra, Kurt. Triumph of the Right: The Rise of the California Conservative Movement, 1945-1966. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1998.

Shadegg, Stephen. What Happened to Goldwater? The Inside Story of the 1964 Republican Campaign. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1965.

White, F. Clifton and William J. Gill. Suite 3505: The Story of the Draft Goldwater Movement. New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1967.

White, F. Clifton and William J. Gill. Why Reagan Won: A Narrative History of the Conservative Movement, 1964-1981. Washington, D.C.: Regnery, 1981.

Wills, Gary. Reagan’s America: Innocents at Home. New York: Doubleday, 1987.

[1] John B. Kilroy, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, February 12, 2011.

[2] Ronald Reagan, An American Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990), 139-140. For other books dealing with the 1964 election, see the Bibliography Section in this post.

[3] Carl Greenburg, “GOP Planning $1,000-a-Plate Dinner Series, Los Angeles Times, September 2, 1964, 3.

“Miller Slated to Talk Here on Thursday,” Los Angeles Times, September 30, 1964, 7.

[4] Steven D. Edgington and Lawrence Brooks De Graaf. The "Kitchen Cabinet": four California citizen advisers of Ronald Reagan: Interviews (Oral History Program, California State University, Fullerton, 1983), 114. “Miller Slated to Talk Here on Thursday,” Los Angeles Times, September 30, 1964, 7.

[5] Curtis Patrick, Reagan: What Was He Really Like? Volume 1 (Kindle edition) (New York: Morgan James Publishing, 2011), 302.

[6] Curtis Patrick, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, September 26, 2014.

[7] Carl Greenberg, “Goldwater to Kick Off State Drive Sept 8,” Los Angeles Times, August 23, 1964, D1. For Reagan’s campaign duties see: Reagan, An American Life, 139.

[8] Reagan, An American Life, 139-140.

[9] Reagan Foundation YouTube video of A Time for Choosing: http://youtu.be/qXBswFfh6AY.

Articles mentioning John B. Kilroy: “Where the Money Is,” Newsweek, May 17, 1965, 39-40. David S. Broder, “G.O.P. Film Lacks a G.O.P. Sponsor, New York Times, July 2, 1965. Walter Pincus, “Goldwater Funds Still Used,” Washington Evening Star, September 15, 1965, A-5.

Kurt Schuparra, Triumph of the Right: The Rise of the California Conservative Movement, 1945-1966 (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1998), 184.

Interview of Gardiner Johnson, California State Archives, Oral History Program, 1973; 1983, 212-215.

[10] Reagan, An American Life, 143. John B. Kilroy, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, February 12, 2011.

[11] Reagan, An American Life, 126-130; 137.

[12] John B. Kilroy, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, February 12, 2011. Peter Raisbeck, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, March 6, 2011.

[13] John B. Kilroy, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, February 12, 2011.

[14] Jim Kilroy, Kialoa US-1: Dare to Win: In Business, In Sailing, In Life (Kittery, Maine: Smith Kerr Assoc., 2012), 78.

[15] Fundraising letter, John B. Kilroy and Patrick J. Frawley, Jr., September 14, 1964, T 36, TV for Goldwater-Miller, Right Wing Collection, University of Iowa.

[16] John B. Kilroy, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, May 15, 2011.

[17] Alexander Zaitchik, “Meet the Man Who Changed Glenn Beck’s Life,” accessed October 26, 2014, http://www.salon.com/2009/09/16/beck_skousen/

[18] “Anti-Red Youth Program,” Press-Telegram (Long Beach, CA), August 31, 1961, A-7. Display advertisement, “Hollywood’s Answer to Communism,” Los Angeles Times, October 16, 1961, B6. Display advertisement, “Anti-Communism Rally,” Los Angeles Times, December 10, 1962, 13.

[19] Peter Raisbeck, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, March 6, 2011.

[20] “In Memoriam,” SAG / AFTRA, Spring 2013, Volume 2, No. 1, 50.

[21] Reverend Doctor Thandeka, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, September 25, 2014.

[22] “Radio and Television Program Reviews,” The Billboard, November 13, 1948, 12.

[23] John B. Kilroy, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, February 12, 2011.

[24] R. Duke Blackwood, e-mail message to Bill Geerhart, September 19, 2014.

[25] EWR & R Conference Report # 31, October 5, 1964, Box 3H514, Goldwater Advertising: Erwin Wasey, Ruthrauff & Ryan Ad Agency, Stephen Shadegg / Barry Goldwater Collection, 1949-1956, Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.

[26] R. Duke Blackwood, e-mail message to Bill Geerhart, October 24, 2014.

[27] Advertisement, Albuquerque Journal, October 27, 1964, A-5.

[28] John B. Kilroy, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, February 12, 2011.

[29] Reagan Foundation YouTube video of A Time for Choosing: http://youtu.be/qXBswFfh6AY

[30] Reagan, An American Life, 140. Edmund Morris, Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan (New York: Random House, 1999), 331. Lee Edwards, Goldwater: The Man Who Made a Revolution (Washington, D.C.: Regnery, 1995), 334.

[31] John B. Kilroy, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, February 12, 2011.

[32] Rick Perlstein, Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 441.

[33] Ibid.

[34] John B. Kilroy, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, February 12, 2011.

[35] Display Advertisement, The Independent (Pasadena, CA), October 23, 1964.

[36] John B. Kilroy, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, February 12, 2011.

[37] EWR & R Conference Report # 45, October 22, 1964, Stephen Shadegg / Barry Goldwater Collection.

[38] EWR & R Conference Report # 46, October 23, 1964, Stephen Shadegg / Barry Goldwater Collection.

[39] Thomas Evans, The Education of Ronald Reagan: The General Electric Years and the Untold Story of His Conversion to Conservatism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), 168-169. Marc Eliot, Reagan: The Hollywood Years (New York: Harmony Books, 2008), 333-334.

[40] Letter from J.J. Wuerthner, Jr. to Michael Deaver, May 4, 1984, Lemuel R. Boulware Papers, University of Pennsylvania.

[41] Peter Kihss, “Goldwater Exhorts 18,000 in Garden ‘Victory’ Rally,” New York Times, October 27, 1964. EWR & R Conference Report # 45, October 22, 1964, Stephen Shadegg / Barry Goldwater Collection. “1964 Campaign Receipts and Spending Reported by 164 Groups,” Congressional Quarterly, January 21, 1964, 72.

[42] EWR & R Conference Report # 46, October 23, 1964, Stephen Shadegg / Barry Goldwater Collection.

[43] Goldwater Spot on being Imprudent and Impulsive: http://youtu.be/k3t6aptzn2A; Goldwater Spot on Communism: http://youtu.be/Uyzg0pPkFNc?list=UUuOUjQf3K8r6XmDhPBGiTJQ; Conversation at Gettysburg Spot: http://youtu.be/Lly3jANwMZM?list=UUuOUjQf3K8r6XmDhPBGiTJQ.

[44] EWR & R Conference Report # 46, October 23, 1964, Stephen Shadegg / Barry Goldwater Collection. Val Adams, “G.O.P. Pre-Empts ‘T.W.3’ A 4th Time,” New York Times, October 24, 1964.

[45] Reagan, An American Life, 141. Edwards, Goldwater, 335. Perlstein, Before the Storm, 500.

[46] J. William Middendorf II, A Glorious Disaster: Barry Goldwater’s Campaign and the Origins of the Conservative Movement (New York: Basic Books, 2006), 207.

[47] John B. Kilroy, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, February 12, 2011.

[48] Middendorf, A Glorious Disaster, 207.

[49] Review of all EWR & R Conference Reports in Stephen Shadegg / Barry Goldwater Collection.

[50] Bruce Weber, “Art Gilmore, the Voice of Coming Attractions, Dies at 98,” New York Times, October 2, 2010.

[51] Arbitron Ratings, Broadcasting, November 2, 1964, 59.

[52] Accounts of the reaction and CONELRAD’s examination of telegrams and letters.

[53] Lucille Boston, e-mail message to Bill Geerhart, April 9, 2011.

[54] Telegrams, Box C35, Folder “66: ‘The Speech’ 1964 (Telegrams in Response)” 1-3, Ronald Reagan Governor’s Papers. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. Telegrams, letters, phone call notes, Boxes 12-13, “TV, Ronald Reagan Speech for Senator Goldwater,” Dean Burch Papers, Arizona State University, Tempe.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Display advertisement, Washington Evening Star, October 31, 1964, A-7. “A Time for Courage,” John Wayne final dialogue script, Folder 7, Box 23, Barry Goldwater Collection, Arizona Historical Society.

[57] Reagan, An American Life, 143.

[58] John B. Kilroy, telephone interview with Bill Geerhart, February 12, 2011; Perlstein, Before the Storm, 500.

[59] Kilroy, Kialoa US-1, 79. Note: Kilroy refers to the bank that processed the contributions as the “Security Pacific National Bank.” Per “Committee Expenditures,” Congressional Quarterly, January 21, 1966, 47, the bank was Security First National Bank.

[60] Reagan, An American Life, 143. Stephen Hess and David S. Broder, The Republican Establishment (New York: Harper and Row), 253.

[61] “Record $47.8 Million Reported Spent in 1964 Elections,” Congressional Quarterly, January 21, 1966, 57-58.

[62] Walter Pincus, “Goldwater Funds Still Used,” Washington Evening Star, September 15, 1965, A-5. Carl Greenberg, Reagan Announces He’s Candidate for Governor,” Los Angeles Times, January 5, 1966, 3.

[63] “Man of the Year,” Time, January 5, 1981, 11.

[64] “Where the Money Is,” Newsweek, May 17, 1965, 39. “Founder, chairman of Kilroy Realty Retires,” Associated Press via Yahoo News, February 28, 2013.