“I can only give you what I have in the way of unclassified information. No one’s ever debriefed me or anything, so I can’t get into the mysterious stuff.”

-John J. Londis to CONELRAD, December 3, 2012

INTRODUCTION

On May 31, 1992, the Washington Post revealed the existence of a classified government bunker under the Greenbrier resort hotel in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. The massive structure—which became operational in early 1962—was intended for the United States Congress in the event of a Cold War crisis. But until the Post story ran only a small number of senior lawmakers knew about the facility. The bunker was maintained for thirty years by Forsythe Associates - a front company staffed by highly trained government employees posing as television repairmen (who actually did fix the hotel’s TV sets in addition to performing their day jobs).

Ted Gup, the dogged journalist who exposed the unlikely hideaway, interviewed many people with detailed knowledge of the relocation site, but when he called Forsythe’s first general manager, John J. Londis, he received a canned response that was older than the bunker’s C-rations. Mr. Londis, who was then 76 and retired, told the reporter that his only function was to service the resort’s televisions.[1] Twenty years later CONELRAD decided to take another crack at the TV repairman who once held a top secret security clearance. We were delighted to find that he was willing to talk and had a lot to say.[2]

SELF-MADE MAN

At 96 John J. Londis still has his Brooklyn accent and a warm sense of humor. He lives in a retirement residence in Florida and spoke with us on the telephone after we introduced ourselves to his son, James. The former Forsythe man, who has a remarkably solid long-term memory, was at first wary of our questions and told us that he couldn’t discuss what he called “the mysterious stuff.” But by the end of our nearly hour-long conversation, he had given us a rare insight into what it was like to work in the Strangelovian West Virginia complex for sixteen years (1960-1976).

Londis was born in New York City in 1916 and dropped out of Brooklyn’s Abraham Lincoln High School because he was a young man in a hurry to enjoy success. “I never graduated high school, really,” he told us, “I took a lot of correspondence courses and I got an equivalency, but I never graduated from a regular high school.” [3]

After his abbreviated education and during the early part of his first marriage, Londis tended bar on Wall Street for several years in the late 1930s. It was at this saloon that he noticed some people who were more generous than most with their cash (a rarity during the Great Depression). He soon learned that these men were employed by International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT) and were working under contract to the U.S. military. The ITT fellows took a liking to their barkeep and arranged for him to learn their teletype system after hours. It was not long after this ad hoc training that Londis quit his bar job and began working for ITT in an entry level position. He was making less money, but he saw a far brighter future in the field of communications than he did in shaking martinis. He remained at ITT throughout the war years.

After Londis separated from his wife around 1947, he left Brooklyn for California where he took an intensive array of courses in electronic communications and technology. As a result of this study, he earned a certification that made him highly marketable as America was entering its long twilight struggle with the Soviet Union. But he was still having trouble finding a job he liked. [4]

It was Londis’s brother Lou who urged him to come to Washington, D.C. to seek work. Lou had been working at the State Department as a “screener” interviewing Greek immigrants who were coming to the U.S. after the war. Heeding his brother’s call, Londis returned to the east coast in 1949 and, while living with Lou, secured his dream job. “I worked for the Army in communications and cryptography,” he told us. “I worked for the Signal Corps.” [5]

James Londis, John’s son, recalled for CONELRAD how impressed his uncle was with John’s self-propelled progress: “My Uncle Lou, proud and amazed at the same time, said that I needed to understand that my father rose through the ranks to the highest level of civilian rank in the Pentagon on diligence and smarts.” [6]

THE ROAD TO THE GREENBRIER

During the early Cold War scramble to build government bunkers, John J. Londis found himself in high demand as a communications specialist. And his status as a single man with greater mobility made him even more attractive to the government. He explained the selection process to CONELRAD: “Well, it was a question of what job I was doing and what job they needed. And I happened to be single at the time, so it was easy for them to move me around and keep me undercover. So they decided to choose me and I agreed.”

And, as it turned out, Londis’s road to the Greenbrier was paved through Berryville, Virginia, home to the mother of all relocation sites - Mount Weather. Londis recalled, without much enthusiasm, that he lived in Berryville while he was working at the Classified Location: “I was assigned to Communications Center as a communications specialist and cryptographic operations [person]. They needed a communications expert.”

It was in 1960 – two years before the Greenbrier bunker became operational – that Londis began his longest government shelter stint. “I think I got there before the bunker was completed,” he confirmed. “We did a lot of installation of equipment. Et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.” The code word for the bunker at this stage was Casper. When asked about the origins of this name Londis said with some degree of uncertainty: “I think it was the name of one of the intelligence agency’s children or something like that. They figured that was a good name. I don’t know.”

When we inquired about the paintings of nature scenes reported to have been placed inside the bunker, Londis told us: “It was our idea. After we got in there, we thought we would brighten it up a little bit. It was bad enough being under there – no windows, no nothing - we were trying to brighten it up. I forget whose idea it was – it was just natural that we’d want some brightness in the place.” [7]

FORSYTHE ASSOCIATES

“Yeah, well that was my cover story, yeah. Branch manager of Forsythe was my cover story.”

-John J. Londis to CONELRAD, December 3, 2012

When the Greenbrier bunker opened for business, so, too, did its front company, Forsythe Associates. With regard to the faux business’s origins, Londis told us that it was devised by the Army: “Well, we didn’t come up with it. Actually, the intelligence people came up with the cover story. It was the Army intelligence people who came up with the story.” When asked whether there was any special significance to the name “Forsythe,” he answered: “No, not really,” and then he revealed “The [company] address in Arlington [Virginia] was false anyway. I think for a while they rented office space up there and after that they just closed it up.” [8] However, for the entirety of the bunker’s secret existence, Forsythe maintained an entry in the Arlington, Virginia telephone book with a real telephone number. [9]

We asked Forsythe’s former “branch manager” what would happen if someone called the number and offered the business real work. “We would tell them that we were too busy for small things,” Londis said. “We always made some kind of excuse.” [10]

In addition to an address and a telephone number Forsythe also had a payroll operation. According to Londis, the Army would deposit funds into the front company’s account and he would then receive his regular paychecks as issued by Forsythe. [11]

He also had a secretary to help him with Forsythe and bunker business. Early in his tenure, Londis hired a West Virginia native named Gladys Childers for this sensitive work. In our interview, we asked him about how he came to choose her and he replied: “I recruited her – I remember that. I picked her – I had a choice of three and I decided to take her because she knew nothing about the government and cryptographic operations and, you know, I could teach her. Someone else –their old habits might interfere with operations.” [12]

Ms. Childers, who declined to be interviewed for this article, presented Londis with a local “boss of the year” award in 1969. The small newspaper article announcing the honor refers to him as “branch manager of Forsythe Associates at White Sulphur Springs.” [13] Childers remained with Forsythe long after Londis retired and, indeed, later gave tours of the bunker when it was opened to the public in the 1990s.[14]

BUNKER STORIES

The bunker became operational a few months before the Cuban missile crisis in October of 1962.[15] We asked Londis about this tense period and whether the facility was ever activated. “Well, the word ‘activation’ means a lot,” he explained. “The system itself was in operation all the time and activated. Personnel were not stationed there for security reasons. During the Cuban missile crisis everybody was alerted to stand by and don’t leave your house. Or if you go anywhere, let us know. And if we needed them, we’d call them, but we never did call them.” Londis confirmed that during other crises like the 1963 Kennedy assassination and the Northeast blackout of 1965, he would remain—sometimes all night long—in the bunker waiting for a telephone call. “If there was going to be one,” he added for emphasis, “yeah.” [16]

It was during this early period at the Greenbrier that Londis remarried. His new wife, Kalla, was a French tutor for the CIA and had a sufficient security clearance to be informed of her husband’s real job. Londis told us that “She was briefed that the government had an interest there, but nobody was really told who it was for.” Kalla passed away in 2011. Londis’s children did not know about their father’s secret occupation until they read about it in the Washington Post in 1992. [17]

The year after the Cuban missile crisis the government sent a new man to supervise the bunker and, understandably, Londis was less than thrilled with the move. Fred C. Hicks, Jr. arrived sometime in 1963 and took control of the facility and Forsythe Associates.[18] When asked about the circumstances of Mr. Hicks’s arrival, Londis became a little exasperated:

“[Congress] made him the top dog down there, but he didn’t do anything, really… He was there as my boss. Initially, he didn’t come down there. Initially, the Army had the full responsibility for the operation, but then somebody in Congress decided they wanted their representative down there which was ridiculous because he really wasn’t needed and he didn’t do anything.” [19]

Hicks, who died suddenly of a heart attack in 1971, is no longer around to defend his work ethic, but CONELRAD recently interviewed his son, Fred C. Hicks III. Among many other details about the site and his family, Hicks revealed to us that his father had a reciprocal disdain for Londis.[20] CONELRAD will be publishing our profile of the late Mr. Hicks in the near future.

Hicks was replaced as manager of the site in short order with Paul E. “Fritz” Bugas. Londis sounded less annoyed when we brought up his new boss’s name, but he quickly digressed into a defense of the importance of communications—his domain—in the bunker. “The communications had to be working all the time,” he declared, “that was the key thing.” [21]

Bugas managed the bunker for the remainder of its classified existence and was later responsible for helping transition the site into a public attraction. He is now retired. [22]

When asked if many VIPs visited the Greenbrier during his career there, Londis replied “Well, [Vice President Hubert] Humphrey used to come down a lot.” In response to our follow-up question about whether the vice president toured the bunker itself, he said with a laugh, “Yeah, he visited the bunker – under cover of darkness.” Londis added that Humphrey was impressed with what he saw: “He was very satisfied that if the need ever occurred that we had the necessary communications equipment and the necessary people to provide them with the communications they might need.” According to Londis, the Greenbrier bunker was the designated relocation site for the vice president. [23]

Over the years Londis gave other bunker tours to senior congressional leaders who had a vested interest in the facility, but he was doubtful that the rank and file members knew about it. “Except for the leadership, I don’t think the congress knew where they were to go,” he told us. “That would have been last minute information.”

On the subject of family and whether the thought of leaving his wife in the event of a national emergency weighed heavily on his mind, Londis surprised us with the following response: “Not really. You get used to that kind of life and you tell your wife to come to the hotel and stay there. Then if it got dangerous enough, you’d grab her and bring her down to the bunker.” When asked to confirm what he had just said, he added: “Well, we were alerted for stuff like that. In other words, we had plans to do something. You can’t ask a man to leave his family and come down to the bunker while the bombs are falling all around him.” Londis claimed that this remarkable contingency plan was part of an official policy, but based on all other accounts, families were not on the formal bunker guest list. [24]

LIFE AFTER THE BUNKER

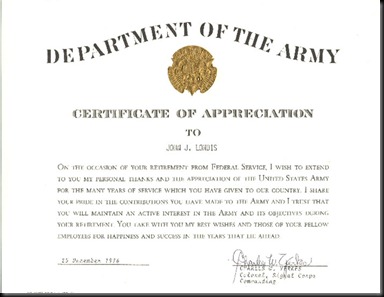

John J. Londis retired from the government and from Forsythe Associates in December of 1976. Colonel Charles W. Yerkes of the Army Signal Corps (he was also an officer at Mount Weather) signed Londis’s Certificate of Appreciation thanking him for his “many years of service.” [25]

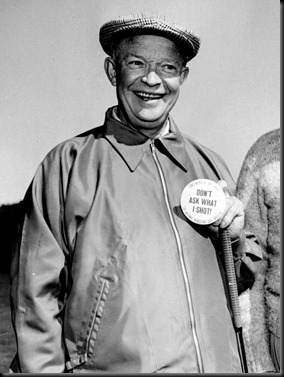

Until they moved to Boca Raton, Florida in the 1980s, John and Kalla remained in their White Sulphur Springs home and availed themselves of the amenities of the Greenbrier resort. Londis, an avid golfer, especially enjoyed the world class links (that is him at the Greenbrier, second from the right, in the photo below). He did not remain in touch with his former Forsythe boss, Fritz Bugas, and never took a tour of the public incarnation of the bunker.

When the Washington Post article was published and exposed the facility and Forsythe Associates, James Londis recalled that he had to call his father to cajole him into talking about it. James was impressed that his dad could keep such a monumental secret for so long: “It surprised and pleased me that he never breached his security oath.” [26]

Indeed, John J. Londis was quite modest in discussing his unique and largely secret role in Cold War history. In summing up his job he told us: “Well, it wasn’t the flashy, elaborate assignment that people might think. It was a hush-hush thing.” [27]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CONELRAD would like to thank John J. Londis for his time and candor in looking back at his long career. It is an invaluable record to have for future generations. We would also like to thank James and Dolores Londis for trusting us with John’s story and providing some additional information about his life. Thanks also to Fred C. Hicks III for additional background information. We would also like to offer a special thanks to Dr. Robert S. Conte, the Greenbrier’s staff historian, and to Ted Gup, the man most responsible for opening the Greenbrier’s giant blast doors to history.

Note: All images used in this post are the property of CONELRAD.com and may not be reproduced without written permission.

This post was updated on March 4, 2013 to reflect additional information provided by the Londis family.

[1] Ted Gup, “The Ultimate Congressional Hideaway,” Washington Post, May 31, 1992.

[2] Telephone interview with John J. Londis conducted by Bill Geerhart, December 3, 2012.

[3] Ibid.

[4] E-mail from James Londis to Bill Geerhart, March 3, 2013.

[5] E-mail from James Londis to Bill Geerhart, March 3, 2013. Telephone interview with John J. Londis conducted by Bill Geerhart, December 3, 2012.

[6] E-mail from James Londis to Bill Geerhart, December 4, 2012.

[7] Telephone interview with John J. Londis conducted by Bill Geerhart, December 3, 2012.

[8] Ibid.

[9] CONELRAD examined, at random, Arlington and Northern Virginia telephone books published during the period of the bunker’s operation (1962 – 1992). We discovered entries for Forsythe Associates through 1992, the year that the bunker was revealed by the Washington Post. In 1993 there was no listing for Forsythe Associates.

[10] Telephone interview with John J. Londis conducted by Bill Geerhart, December 3, 2012.

[11] Email from James Londis to Bill Geerhart, December 2, 2012.

[12] Telephone interview with John J. Londis conducted by Bill Geerhart, December 3, 2012.

[13] “Londis Is Cited,” Beckley Post-Herald (West Virginia), April 24, 1969, page 20.

[14] Gladys Childers is documented as still being employed with Forsythe in Gup’s article (see end note 1). Her role as a bunker tour guide was confirmed to CONELRAD’s Bill Geerhart by Greenbrier historian Dr. Robert S. Conte on November 14, 2012.

[15] Ted Gup, “The Ultimate Congressional Hideaway,” Washington Post, May 31, 1992 and Dr. Conte Robert S. Conte, “Hidden in Plain Sight: The Greenbrier’s Bunker,” Goldenseal, Winter 2010, page 21.

[16] Telephone interview with John J. Londis conducted by Bill Geerhart, December 3, 2012.

[17] For John and Kalla Londis’s marriage and Kalla’s profession: E-mail from James Londis to Bill Geerhart, February 25, 2013. For clearance quotation: John J. Londis telephone interview conducted by Bill Geerhart, December 3, 2012. For adult children’s discovery of father’s true occupation: E-mail from James Londis to Bill Geerhart, December 4, 2012.

[18] Interview with Fred C. Hicks III conducted by Bill Geerhart, January 23, 2013.

[19] Telephone interview with John J. Londis conducted by Bill Geerhart, December 3, 2012.

[20] Interview with Fred C. Hicks III conducted by Bill Geerhart, January 23, 2013.

[21] Telephone interview with John J. Londis conducted by Bill Geerhart, December 3, 2012.

[22] Mr. Bugas’s bunker transition role and current retirement status was confirmed to CONELRAD’s Bill Geerhart by Greenbrier historian Dr. Robert S. Conte on November 14, 2012.

[23] Telephone interview with John J. Londis conducted by Bill Geerhart, December 3, 2012. CONELRAD was able to find evidence of Vice President Hubert Humphrey visiting the Greenbrier in June of 1965 through the archives of the Chesapeake and Ohio Historical Society.

[24] Telephone interview with John J. Londis conducted by Bill Geerhart, December 3, 2012. For policy of families not being permitted in the bunker, see Gup’s article (end note 1).

[25] The date of John Londis’s retirement is documented in the copy of the Certificate of Retirement provided to CONELRAD by James Londis. For Colonel Yerkes role at Mount Weather see “Mrs. Yerkes Considered For PHW President,” Winchester (Virginia) Star, January 29, 1983, page 2.

[26] E-mail from James Londis to Bill Geerhart, December 4, 2012.

[27] Telephone interview with John J. Londis conducted by Bill Geerhart, December 3, 2012.

![JFK-TV[3] JFK-TV[3]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgfiA9qOznuI1WUO5bZsH68jwSPEXgxbZxtzck4e5w_3xpHIiyd3EH9VKbTlFybgshzKf6omH8CU3rw1Wrv-RVQBk8W2Ru6v20xAndZNnstydf9WS7xlb_hQUsxNbBs4BNs34tK86SRmSg/?imgmax=800)