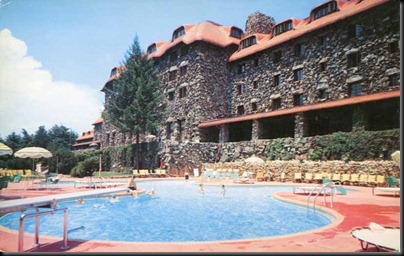

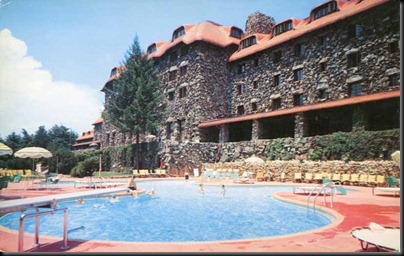

In 1992 the Washington Post revealed to the world the surprising Cold War emergency relocation plan of the United States Congress. In remarkably detailed reporting the newspaper told the Strangelovian story of a massive government bunker built beneath the posh Greenbrier resort in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia in the late 1950s.[1] The irony of lawmakers riding out World War III under a five star hotel while the public sheltered in place was hard to miss. Needless to say, CONELRAD was intrigued to find, years later, a reference to the U.S. Supreme Court’s oddly similar contingency plan in David Krugler’s impressively researched 2006 book This Is Only a Test: How Washington D.C. Prepared for Nuclear War.[2] Indeed, based on previously published news articles we had assumed that in the event of an emergency the Justices would have been whisked away to Mount Weather, the impregnable crown jewel of the Federal Relocation Arc.[3] But Krugler had discovered evidence proving that the Court had secured nicer—if significantly less fortified—accommodations at the historic Grove Park Inn in Asheville, North Carolina. When we contacted the author to see if he had a copy of the April 1956 agreement between the Supreme Court and the hotel, he told us that he had not come across that crucial document – only memoranda that referred to it. That was all we needed to hear. The search was on.

CONELRAD’s next call was to the Grove Park Inn to ask the management if they possessed the elusive contract. The representative we spoke with was uncertain as to whereabouts of the document but he helpfully referred us to Bruce E. Johnson who has written extensively about the resort. “If anyone would know about it,” the representative said, “Bruce would.”[4] Mr. Johnson informed CONELRAD that he had, in fact, seen the contract along with some additional government correspondence while going through the hotel’s archives to research his book Tales of the Grove Park Inn (the author devotes two paragraphs to the extraordinary government arrangement on page 313).[5] Unfortunately, Johnson did not have a copy of the contract – only his notes. Before contacting the hotel again, we decided to engage in a broader search of the Supreme Court records held at the Library of Congress where Professor Krugler had originally found the memos referencing the agreement. We also examined federal civil defense records at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. And, while we were unable to locate the contract itself at these facilities, we did uncover other important documents that inform this article. We were now ready to travel to North Carolina.

On March 29th we were permitted access to the Grove Park Inn’s archives. Johnson had warned us prior to the visit that the records—which are kept in a large filing cabinet in the hotel’s back office—were not well organized.[6] But, as it turned out, CONELRAD’s Bill Geerhart was able to find the contract quickly – it was in a blue binder labeled “Historic Memorabilia 1955-1969.”

The weathered photocopy of the April 3, 1956 contract (more specifically a “Letter of Understanding”) is attached to a cover letter that was sent from the corporate office to the Grove Park Inn so that the document could be “kept on the property in the event there is none there right now.”[7] It is fortunate for history that this step was taken because government copies of the contract have since been either destroyed or classified.[8]

This remarkable document, published here for the first time, is short and sweet. The two page letter provides that “In the event of an enemy attack or the imminence thereof,” the Supreme Court would “take possession of the facilities described in Exhibit ‘A.’ Along with other particulars, the attached exhibit describes the hotel as having 141 rooms, 4 cottages and a 40 room dormitory. The author of the agreement also—perhaps a bit too optimistically considering the effects of atomic war—includes a provision for a “formal lease” to be negotiated “as soon as possible, thereafter.”[9] Reflecting the open-ended nature of the Cold War in 1956, there is no specified expiration date in the contract. This is an omission that would cause headaches later.

Supreme Court / Grove Park Inn Contract - 04/03/1956 by Bill Geerhart

OFFICE OF THE CLERK

Supreme Court of the United States,

Washington 13, D.C.

April 3, 1956

Grove Park Inn,

Asheville, North Carolina

Gentlemen:

Reference is made to the confidential discussions heretofore had between our respective representatives. In pursuance thereof, the United States of America, acting by and through The Supreme Court of the United States, represented by the undersigned as contracting officer, hereby proposes to acquire the right to use and occupy the facilities described in the enclosure hereto, marked Exhibit “A”, as hereinafter provided.

In the event of an enemy attack or the imminence thereof and upon notice verbal or written to such effect, by an authorized representative of the Government, it is understood and agreed that you will permit The Supreme Court of the United States immediately to take possession of the facilities described in Exhibit “A”. As soon as possible thereafter, the Government will enter into negotiation with you for the execution of a formal lease covering the rights and obligations of the parties with respect to the aforementioned facilities and providing fair compensation for the use thereof the Government commencing with its initial occupancy. Such formal lease or other instrument will be negotiated by General Services Administration. All prior conversations or negotiations between our representatives are merged in and superseded by this letter.

It is understood and agreed that the Government will not be responsible for any expenses incurred by you prior to the period covered by the formal lease or other instrument to be hereafter negotiated.

It is further understood and agreed that from time to time due to changed conditions, it will be necessary to amend or supplement Exhibit “A” by the addition or deletion of facilities therefrom.

Please indicate the acceptance by your governing body of the foregoing by signing and returning to us the original and two copies of this letter. A copy is attached for your files.

Sincerely yours,

Harold B. Willey, Clerk

Contracting Officer

Accepted, as of the date of this letter.

Hotel Operating Co

By EC Leach

Attorney in Fact

The man who signed the agreement on behalf of the Grove Park Inn (or more technically, the Hotel Operating Company) was Edward C. Leach, Sr., the president of the Texas-based Jack Tar Hotel chain that owned the Grove Park Inn at the time. Leach died in 1996 at the age of 83. His son, Edward C. Leach, Jr., a Charlotte, North Carolina attorney, told CONELRAD that his father never mentioned the top secret arrangement with the Supreme Court and that prior to our phone call he had never known about it.[10]

Why was the luxurious, but bunker-less Grove Park Inn chosen to host the Supreme Court Justices and their staff during a crisis? One of the aforementioned document discoveries by CONELRAD answers this critical question. The year before the contract was formally agreed to, Harold B. Willey, the Clerk of the Supreme Court—and the man who signed the contract on behalf of the government—visited Asheville, North Carolina on a scouting mission.

Shortly after his return to Washington, D.C. in October of 1955, Willey summarized his findings for the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Earl Warren. The letter, which is published below for the first time, includes the explanation that General Paul of the Office of Defense Mobilization (ODM) suggested Asheville as a “likely site for us.”[11] CONELRAD has identified the referenced official to be Lieutenant General (Retired) Willard S. Paul. Paul had been recruited to the ODM in 1954 by the director of the agency, Arthur S. Flemming.[12]

The clerk uses the next couple of paragraphs of his letter to lay out the finer points of Asheville and its desirability as a relocation site. He explains that the town is “served by Capital Airlines and the Southern Railway” and goes on to reason that “Because all large cities are considered to be enemy targets, a hotel in a secluded small city wherein approximately one-hundred people could both live and work, with spaces available for a court room and clerical offices, seems a most appropriate facility for the court.” Willey then cites his rationale for recommending the Grove Park Inn over the other major hotels in Asheville (the Battery Park and the George Vanderbilt). His reasons run the gamut from the practical—the hotel has large conference rooms that can be converted into courtrooms and libraries—to the frivolous: the hotel has plans to build a swimming pool and there is a golf course that adjoins the property.[13]

Grove Park Inn Selected as Relocation Site: 1955 by Bill Geerhart

In the end, Willey went beyond merely recommending the Grove Park Inn to the Chief Justice. Indeed, he obtained a letter from the manager indicating that the owners of the hotel were “receptive to the idea” of the Court relocating there and he attached a draft “Letter of Understanding” to the letter that he submitted to Warren [Editor’s note: the attachments were not found by CONELRAD].[14] But the always prudent Chief Justice turned to a colleague on the bench for an in-house legal review of the matter before moving forward. On a note card, Justice Harold Hitz Burton succinctly stated:

Dear Chief –

I have examined the attached material and believe it presents a reasonable solution on its face.

HHB[15]

The following year, on June 6, 1956, Willey—who was retiring as clerk—notified Warren that the “letter of understanding” with the Grove Park Inn had been signed and that a copy had been distributed to General Paul, the civil defense official who had set everything in motion in the first place.[16] The Chief Justice was “pleased” with the progress and asked Willey to discuss with the incoming clerk, John T. Fey, plans “for actually establishing the Court at Asheville should the need to do so confront us.”[17] Very little was ever done in this regard. According to an undated draft letter by Supreme Court Clerk John F. Davis to Edward A. McDermott, Director of the Office of Emergency Planning, “No steps” had been taken “to provide the facilities and supplies…which the Court would require to function as a court.” Davis further explained in his draft that “It has been thought that the facilities of the United States District and Circuit Courts at Asheville probably would be available for our use, but they are limited and certainly would not enable the Court to perform its regular functions.” Finally, Davis wrote that “Each spring the Marshal of this Court sends to the Clerk of the District Court at Asheville a microfilm copy of the Marshal’s payroll records, but I believe these are the only records which have been forwarded.”[18]

Mr. McDermott, the intended recipient of Davis’s draft letter, had met with the Chief Justice at the Supreme Court building during the Cuban missile crisis in an apparent effort to make the case for the superiority of Mount Weather as a relocation site. McDermott summarized the meeting in a semi-redacted letter to Warren dated October 30, 1962.[19] It was not the only time during the missile crisis that the Chief Justice had been told about the assigned space for the Court at the super bunker in Virginia. CONELRAD interviewed Ramsey Clark who was then the Assistant Attorney General (he also happened to be the son of sitting Supreme Court Justice Tom C. Clark) and he revealed to us that Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy had assigned him to tour Mount Weather during the missile crisis. The purpose of the visit was to review the Supreme Court’s accommodations there and to then brief Earl Warren. When asked to describe what awaited the Justices at the site, Clark told us:

“Well, it was cramped. It wasn’t a grade A hotel. I saw beds. I don’t think they were double-deckers. It was like camping out – only with a lot of metal and concrete.”

According to Clark, after he filled the Chief Justice in on the facility and their relocation protocol, Warren turned to him and said “Ramsey, I’m not going to relocate, I’m going to stay with my family.”[20]

CONELRAD was unable to find any records to indicate that the Supreme Court Justices ever went to the Grove Park Inn as a group.[21] And if the Justices had decided to evacuate to the North Carolina resort during the Cuban missile crisis there may have been complications. CONELRAD found documents in the hotel’s archive that prove that the Grove Park Inn had double booked their disaster accommodations for a short, but very critical period, during 1962. Specifically, on August 9, 1962 the hotel entered into a public Fallout Shelter agreement with the Buncombe County United Civil Defense Director, Nora Gunter. It was not until February 15, 1963 that Edward C. Leach, Sr. informed Ms. Gunter of the mistake:

“When I was in Asheville recently, I discovered that inadvertently we had entered into an agreement with you regarding the use of the Inn as a Civil Defense fallout shelter. I must advise, however, that when Mr. [Rodney S.] Morgan entered into this agreement with you that he was unaware of a prior commitment we have to the Supreme Court of the United States for their use of our building in the event of such an emergency.” [22]

Ten years after the original contract was signed, a representative of the Grove Park Inn asked the Supreme Court if they wished to continue their relocation agreement with the hotel. It had been four years since the Court had last confirmed its desire to continue the arrangement (at the height of the Cuban missile crisis). In this instance, however, Chief Justice Warren simply advised John F. Davis to ask “whoever is in charge of [federal] Civil Defense” for their advice on how to proceed.[23] CONELRAD was unable to locate any documentation related to the guidance the Court may have received.[24] We were left to wonder then whether the Supreme Court was still slated to evacuate to Asheville, North Carolina in the event of an emergency. So we asked both parties if the contract is still in effect.

A representative of the Public Information Office of the Supreme Court informed us via email that “The Court does not comment on security operations as a rule.”[25] And Tracey Johnston-Crum of the Grove Park Inn told us that “The Grove Park Inn would certainly defer to the decision of the Supreme Court.”[26] CONELRAD has notified the Court that their rooms are still reserved and that the swimming pool has been completed.[27]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost CONELRAD would like to thank David Mead and Hilary Thomas of the Grove Park Inn for allowing Bill Geerhart to examine the hotel’s archives to find the document that is the primary focus of this article. Mr. Mead and Ms. Thomas took time out of their day during a very busy week to humor what must have seemed like a rather odd request. We are truly grateful for their kind hospitality. We would also like to thank David Krugler who was the first person to write about the existence of the contract between the Grove Park Inn and the U.S. Supreme Court. Without Professor Krugler’s initial research, we would not have had the roadmap to the documents that we ultimately found. Finally, thanks to Bruce E. Johnson for providing confirmation that the contract did, in fact, reside in the Grove Park Inn archives. Mr. Johnson was also very generous with his time in answering our questions regarding the history of the hotel and its staff.

[1] Ted Gup, “The Ultimate Congressional Hideaway,” Washington Post, May 31, 1992. Note: The Post’s D.C. rival, the Washington Times, tried to steal some of the newspaper’s glory by reporting on the Post’s scoop on its front page the day before.

[2] David Krugler, This is Only a Test: How Washington D.C. Prepared for Nuclear War [New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006] p.7; p. 168.

[3] Ted Gup, “The Doomsday Blueprints,” Time magazine, p. 35, August 10, 1992. Gup, “How the Federal Emergency Management Agency learned to stop worrying—about civilians—and love the bomb,” Mother Jones, January 1, 1994. “Very Important People,” New York Times, November 1, 1992.

[4] David Mead of the Grove Park Inn to Bill Geerhart during a January 8, 2013 telephone conversation. Bruce E. Johnson’s books about the Grove Park Inn: Built for the Ages: A History of the Grove Park Inn [Asheville, NC: Grove Park Inn, Revised Edition, 2013] and Tales of the Grove Park Inn [Fletcher, NC: Knock Wood Publications, 2013].

[5] Bruce E. Johnson to Bill Geerhart during a January 8, 2013 telephone conversation. For reference to the Grove Park Inn’s contract with the Supreme Court, see page 313 of Johnson’s Tales of the Grove Park Inn.

[6] Bruce E. Johnson to Bill Geerhart during a January 8, 2013 telephone conversation.

[7] The photocopy of the April 3, 1956 contract and other documents related to the hotel’s agreement with the U.S. Supreme Court were found in the Grove Park Inn Archives, Asheville, North Carolina, in a binder labeled “Historic Memorabilia 1955-1969.”

[8] CONELRAD searched the unclassified records of the various federal civil defense agencies at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland and at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, Massachusetts. We also searched the relevant Supreme Court records at the Library of Congress. No copy of the contract was found at these facilities.

[9] Supreme Court / Grove Park Inn contract, April 3, 1956, binder: “Historic Memorabilia 1955-1969,” Grove Park Inn Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[10] For Edward C. Leach, Sr. obituary see The Galveston County Daily News, p. 4-A, June 20, 1996. For Mr. Leach’s comments regarding his father: Bill Geerhart telephone interview with Edward C. Leach, Jr., April 22, 2013.

[11] For October 14, 1955 Willey letter to Warren: Box 399, folder “Clerk: Memos, Orders, et al 1946-1956, Papers of Earl Warren, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division. For more on Harold B. Willey see “Harold B. Willey, Retired Supreme Court Clerk,” Washington Post, p. B6, July 8, 1982.

[12] “News Censorship Mapped for War,” New York Times, November 6, 1954.

[13] For Willey letter to Warren: Box 399, folder “Clerk: Memos, Orders, et al 1946-1956, Papers of Earl Warren, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid. Justice Burton’s note is attached to Willey’s letter.

[16] For June 6, 1956 Willey letter to Warren: Box 399, folder “Clerk: Memos, Orders, et al 1946-1956, Papers of Earl Warren, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division.

[17] For June 12, 1956 Warren letter to Willey: Box 399, folder “Clerk: Memos, Orders, et al 1946-1956, Papers of Earl Warren, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division.

[18] For undated John F. Davis draft letter to Edward A. McDermott: Box 414, folder “Court – Subject File – Marshal Civil Defense,” Papers of Earl Warren, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division. Note: Another document in the same file dated October 26, 1962 states: “The Marshal has done nothing on this matter except to send Photostats of each employee’s retirement card to the Gr Clerk of the District Court at Asheville.” CONELRAD has a pending request with the clerk of the U.S. District Court in Asheville to determine if any of the old records sent by the Marshal of the Supreme Court still exist. If and when we receive a response, we will update this post.

[19] McDermott appointment book entry for October 26, 1962: Collection Number MsC0241, Edward A. McDermott Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University of Iowa. McDermott October 30, 1962 memo to Warren: Box 1, U.S. Office of Emergency Planning, Microfilm, Roll 1, Paper Copies, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston, Massachusetts.

[20] Telephone interview with Ramsey Clark conducted by Bill Geerhart on April 2, 2013. Note: Clark did not know that the bunker had a name, but based on his description of the site and the route that he took to drive there, there is little doubt that he visited Mount Weather. Also supporting the assertion that Clark went to Mount Weather is the previously published material that this is the facility the federal government reserved for the Court (see footnote 3). Also, Edward A. McDermott (the official who met with Warren) was director of the Office of Emergency Planning (OEP). This was the agency responsible for operating Mount Weather during the referenced time period. Ramsey also told us that he was unaware of the Grove Park Inn arrangement.

[21] CONELRAD review of federal civil defense records related to annual Operation Alert drills located at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. CONELRAD also reviewed relevant Supreme Court files at the Library of Congress. CONELRAD also asked author David Krugler if he was aware of any document related to the Supreme Court participating in civil defense relocation exercises. He told us that he was not.

[22] December 13, 1962 memo from Rodney S. Morgan to Edward J. Giusti and February 15, 1963 letter from E.C. Leach to Nora Gunter: binder: “Historic Memorabilia 1955-1969,” Grove Park Inn Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[23] Correspondence related to the re-confirmation of the agreement: October 26, 1962 letter from John F. Davis to Robert H. Francis and Joe R. Woods’ November 26, 1962 response to John F. Davis: binder: “Historic Memorabilia 1955-1969,” Grove Park Inn Archives, Asheville, North Carolina. April 29, 1966 memo from John F. Davis to Earl Warren and Warren’s April 29, 1966 response: Box 414, folder “Court – Subject File – Marshal Civil Defense,” Papers of Earl Warren, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division.

[24] CONELRAD searched the unclassified records of the various federal civil defense agencies at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland and at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, Massachusetts. We also searched the relevant Supreme Court records at the Library of Congress.

[25] Scott Markley, Public Information Office, U.S. Supreme Court to Bill Geerhart via email, April 18, 2013. Note: Markley’s response also offered the location, already in the public domain, of where the Supreme Court heard oral arguments during aftermath of the 2001 anthrax letter attacks (the E. Barrett Prettyman Courthouse of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit).

[26] Tracey Johnston-Crum to Bill Geerhart via email, April 17, 2013.

[27] Bill Geerhart to the U.S. Supreme Court Public Information Office via email, April 23, 2013.