“Oh, we’ve been ready for this for a long time.” He smiled knowingly. “Our country wasn’t so dumb.”

-- Jim Turner, Civil Defense Security Official, to housewife Gladys Mitchell after an atomic attack on the United States in Judith Merril’s Shadow on the Hearth

Note: Spoilers follow. Also, the 1954 television version of Shadow on the Heart, Atomic Attack, is presented in its entirety at the bottom of this post in five parts.

Shadow on the Hearth (1950) was the first published novel by the respected editor and writer Judith Merril (1923-1997). Merril, an important figure in modern science fiction, would devote most of her career to publishing stories and novels in that genre. While not truly science fiction, Shadow on the Hearth, is typical of Merril’s work in that it places a female character at the forefront of the action. Indeed, the protagonist’s husband in Shadow on the Hearth spends 99% of the novel off-page. Given the surplus of post-apocalyptic fiction wherein men are the central figures, Ms. Merril’s debut book is quite unique.

Merril begins her speculative World War III story like the first act of a domestic 1950s situation comedy: A teenage daughter, Barbara, complaining that her mother, Gladys, still calls her by her childhood nickname, Babsie; the younger daughter, five-year-old Ginny, is trying to find a stuffed animal toy named “Pallo” and the husband and father, Jon Mitchell is just trying to finish breakfast and the paper before having to leave for work in the city at his civil engineering consulting company. There is, however, a not-so-subtle clue that lets the reader know that the lives of the semi-oblivious suburbanites are about to change forever. The foreshadowing comes in the description of patriarch’s reaction to the day’s news:

“The headlines jumped at him, bearing threats of war and disaster… the news the paper spoke of existed in another world, not in his home. Gladys never even read the front page; maybe she had the right idea.”

After a few more pages of establishing the flavor of normal day-to-day life in Westchester, New York (husband off to work, kids off to school, mother off to her chores), Merril drops the fictional bombs on Manhattan (and the rest of the country) that will set the stage for the remainder of her engrossing book. Refreshingly, there are no mushroom clouds and the one siren that Gladys Mitchell hears she almost mistakes for a factory whistle. The bombs have been detonated at a distance and the impact they have on the suburbs is eerie and mysterious (rain on one side of the sidewalk, etc.). It is clear from the beginning of Shadow on the Hearth that the story is going to be about human beings and not the dazzling pyrotechnics of atomic war. The “enemy” is never named, but then who else could it have been in 1950? In this way, Merril presaged another dramatic and character-driven treatment of nuclear war that came more than thirty years later – the film Testament (1983) directed by Lynne Littman. Like Shadow on the Hearth, Testament has at its center a household left fatherless by a nuclear attack.

The reality that atomic war has broken out doesn’t become real for Gladys until she hears it on the radio:

“… one-fifteen P.M., Eastern Standard Time, this afternoon. It is almost certain that equal damage was sustained throughout the country. The cities outside the radius of two hundred miles, roughly, have not yet been heard from. Transcontinental wires are down and radiations appear to be interfering with radio communications in all directions.”

“Flash! We have received our first report, since the bombing, from Washington, D.C. The Capitol was hit by at least one bomb at about one-thirty today. The larger part of the governmental area has—“

“… For those of you who have just tuned in, we repeat: several atomic bombs of unknown origin landed in and near the harbor of New York City this afternoon.”

The chatter of various radio announcers reporting on the attack, the progress of the short-lived war and the activities of the local and national civil defense authorities is threaded throughout the novel. And the understated subversiveness of Merril’s writing is evident from the moment she describes Gladys’s dismissive opinion of the stentorian-toned broadcasters. As the book progresses, the author’s critique of the infrastructure of civil defense and government becomes more pointed.

When Gladys’s daughters return to the Mitchell home apparently unscathed, the author begins her mostly house-bound narrative in earnest. This is not to say that there are no external intrusions because they are constant and they drive the plot forward in some ways like a thriller. In addition to the regular stream of radio dispatches, Gladys must contend with her hysterical neighbor, Edie Crowell, who keeps calling her on the telephone in direct violation of civil defense orders. Ms. Crowell, it seems, thinks she has been exposed to radiation while attending a luncheon during the attack that Gladys skipped at the last minute.

Gladys also has to deal with the remarkably efficient and paranoid Emergency Headquarters staff that rolls into action immediately after the attack. This previously secretive force includes a neighbor, Jim Turner, who is all too eager to embrace his new authority. It is Turner (along with the young Dr. Peter Spinelli) who shows up in a radiation suit at the Mitchell home soon after the bombs go off. He hands out booklets titled “VITAL FACTS FOR CIVILIANS—ATOMIC WAR.” When Gladys remarks on how she never knew about all the preparation the government had taken, Turner replies with prideful bluster:

“Well, nobody else knew either. Nobody who wasn’t in it. When you want to win you got to keep a poker face and play it close to the vest. And any time the government let out any information about what we were doing some scientist would start yelling about warmongers, or some reds would have a demonstration.”

Turner’s partner, Dr. Spinelli, is more reserved in his flag waving and simply wants to get on with his job (collecting urinalysis samples from the residents of the blocks that they are responsible for). The ideological differences between the two men become more pronounced as the story unfolds.

Tellingly, it is not the sanctioned authorities who first warn Gladys about her older daughter’s possible exposure to radiation, it is a blacklisted atomic scientist who also happens to be Barbara’s teacher. Against her better judgment, Gladys allows the man into her house in violation of the never-ending instructions on the radio. He tells Gladys that Barbara may have been doused with radioactive rain during a field trip that he was leading earlier in the day. It turns out that the girl is OK and later Barbara explains to her mother Dr. Garson Levy’s background:

“He knows everything about atom bombs. He was at Oak Ridge and everything… Only he got black-listed or something on account of refusing to do war work, and making a lot of speeches and being on committees, so he had to go be a teacher.”

After some trepidation, Gladys permits Levy to stay hidden in her house, but he more than earns his keep by helping to subdue a home-invading looter with a skillet. He also helps take a blood count from the younger Mitchell daughter, Ginny, when clumps of her blonde locks come out one day as Gladys brushes the girl’s hair.

Another character whose patriotism is questioned is a lower-ranking member of society, the Mitchell family’s maid, Veda Klopak. Veda was found by civil defense authorities huddled in her sealed-off East Bronx rooming house apartment after the attack. The civil defense people don’t believe that Veda sealed her room because she was trying to get over a bad cold. They think she might have been one of the enemy agents who helped set a “radar beacon” to guide the atomic bombs to their targets. After Gladys vouches that her simple-minded maid is not a spy, she is released to her custody, but remains on a watch list.

The Mitchell men exist on the periphery in Shadow on the Hearth. Gladys frequently invokes her husband’s name “Jon” when things become unmanageable (such as when she has to don her husband’s work clothes to go into the basement to turn off the gas valve). “What would Jon do?” Gladys asks repeatedly. The Mitchell’s son, Tom, is a 17 year old freshman at Texas Tech who, we learn from a radio dispatch, is among those mustered into the army to mop up after the retaliatory strikes on the “enemy.” Gladys never wanted Tom to be in the army, but she is relieved to know that he survived the attacks.

With the patriarch and son out of the way, the power-pumped civil defense character, Jim Turner, takes on a more predatory presence. At first Gladys is incredulous that he might have designs on her. When Veda the maid suggests as much, Gladys laughs it off:

“Rinsing her face, Veda’s worried words came back to her, and she chuckled at herself in the mirror, enjoying the picture of Gladys Mitchell, settled mother of three, being wickedly pursued by Jim Turner—beefy face, bedrock convictions and all… She tried to imagine herself cowering before an amorous airtight suit. ‘No, no, a thousand times…’”

But later, it becomes clear that Turner is trying to control the Mitchell family’s evacuation to a civilian relocation camp to his own advantage. Gladys doesn’t want to abandon the family home because she knows staying put is her only hope of ever seeing her husband again. But the loathsome Turner cynically tries to convince her otherwise:

“And you got to get over thinking your hubby’ll come back here. You’ll get to see him a lot sooner at Sampson (the evacuation camp). You just leave it up to me.”

Turner’s abuse of power is one example of the post-attack bureaucracy. The broader fear of government run amok in the post-attack world is summed up by another character: “Things get a little worse, they’re going to realize security is more important than jury trials.”

There is only one trip outside the Mitchell home in the novel proper (there are brief sidebar chapters that give the reader fragmented peeks at the outside world) and it comes after Dr. Spinelli discovers that Gladys has been sheltering the fugitive Dr. Levy. It turns out – rather conveniently – that Levy was a very important figure in the young doctor’s life and career as Spinelli himself explains:

“After all, I was a high school senior, and a science major in Year One of the atom bomb. And I was a college freshman the year Gar Levy was making big noises in the paper with his Survival Kit. I heard him talk several times, and I gave money to his committees. I even managed to get introduced to him at a dinner once. He didn’t remember me, of course, but I’d know him anywhere.”

“I could hardly forget him, seeing that the money I gave and the petitions I signed were largely responsible for making me a doctor. I planned on biochemistry, in connection with radiation therapy. Unfortunately the work you can do in that field is negligible unless you can pass a loyalty check. I got turned down for an atomic scholarship because of my—ah—unfavorable associations, Gar Levy among them.”

It is Gladys’s taking a chance on helping Levy that inspires Spinelli to spirit her and her sick daughter, Ginny, to the hospital where she can get the proper help. As they race to the hospital in Spinelli’s state-issued vehicle, Merill provides this portrait of the post-attack Westchester landscape:

“Nightmare rode with them through the empty streets in the speeding car. Every familiar pattern of the suburban night was gone. There were no late cars coming back from town, no lonely men out walking in the night, no hastily dressed women pulling leashes of their dogs.”

At the hospital Merril treats the reader to a token victim of the bomb, a little boy whose condition startles Gladys and frightens Ginny:

“Bandages covered the boy’s arm, but on the active hands they couldn’t stay in place. Blood and pus ran from a visible open sore; inside his sleeve the bandage was stained with the accumulation from others unseen. His hair wasn’t shaved off, she realized then. There just wasn’t any. And there was something wrong with his face, something that made him look as much younger than his four years as the bald pate made him look older. She placed it at last. No eyebrows. None at all.”

The conclusion of Shadow on the Hearth is a little too neat given some of the provocative themes of control and paranoia that Merril raises during the course of the book. Her husband, wounded because he was mistaken for a looter, does (unlike William Devane in Testament) return (presumably to shut down the advances of Jim Turner once and for all); it is learned that Dr. Spinelli has figured out what caused Ginny’s radiation sickness – it was the stuffed animal referenced in the first carefree pages of the book. Ginny had left it out in the rain. In the Cold War, it turns out, even a kid’s toy can become an instrument of near death as Barbara explains Spinelli’s discovery to her mother:

“Doc found it with the little Geiger counter. Pallo’s a Trojan horse, atomic style. He’s hot—a one-man radioactive rodeo.”

Perhaps most importantly, Merril informs us at the end of her book that America has won World War III. We learn this, as we have learned almost every other piece of news, from the ubiquitous radio announcer:

“Five thirty-seven A.M., Friday, May seventh,” a hoarse voice intoned. “That is the historic moment. We have just received official news from General Headquarters. The war is over! The enemy conceded at 5:37 A.M., Eastern Standard Time, just five minutes ago. Ladies and gentleman, the national anthem!”

Left unsaid is whether the civil liberties taken for granted prior to the attacks will ever be restored. Maybe this implied question was Merril’s unwritten ending.

The reviews for Shadow on the Hearth were mixed and some writers took unwarranted potshots at the intelligence of the protagonist. Indeed, one male reviewer (see excerpted reviews below) referred to Gladys Mitchell as being “vaguely stupid.” Is it possible these reviewers might have felt a little threatened by a novel that had an assertive and challenging female character? A strong case can be made for Shadow on the Hearth being a proto-feminist novel and these characteristics clearly made some people uncomfortable in 1950.

Shadow on the Hearth

By Judith Merril

Copyright 1950 by Judith Merril Pohl

Published by Doubleday and Company, Inc.,

New York

277 pages

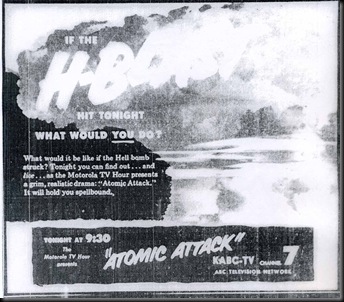

Four years after the publication of Shadow on the Hearth, a television adaptation was broadcast on ABC’s Motorola TV Hour (May 18, 1954, 9:30 P.M.). The title of the episode is the more direct - Atomic Attack - and it features excellent performances by Phyllis Thaxter as Gladys Mitchell and Walter Matthau as Dr. Peter Spinelli.

The script, however, scrubs away all of author Judith Merril’s challenging nuances from the novel and converts the story into a commercial for civil defense. Indeed, prints of Atomic Attack were later used for civil defense instruction and it was listed for rental and sale in government film catalogs from the era.

Thus the once menacing civil defense official Jim Turner from the book is turned into a propaganda tool with the proper officiousness of Joe Friday from Dragnet with dialogue that could have been written by Jack Webb himself:

“Got a new line of work, Mrs. Mitchell, I’m your block warden.” After Gladys marvels at his efficiency, he responds politely, but with a bit of a scold in his tone: “Well, we trained for it long enough. Civil defense – some folks thought it was kid’s game. You know, lots of laughter, just a game. Some game.”

Gone is the novel’s subtext of Turner’s boastful embrace of the power that the catastrophe has conferred upon him. Instead he becomes the one dimensional vehicle for conveying to the 1950s audience that they laugh at civil defense at their own peril.

The blacklisted atomic scientist from the novel, Dr. Garson Levy, is also changed for the purposes of the TV adaptation. Levy becomes “Lee” and he is turned into a religious pacifist who mistakenly thinks he is wanted by the government for subversion. In fact, as Dr. Spinelli reveals in the final act, he is being sought for his scientific abilities to aid the recovery effort. The screenwriter, David Davison, further nullifies the Levy/Lee character by having him pick up a shotgun and shoot at a looter who is trying to break into the Mitchell kitchen. When he laments the action he has just taken, Gladys chastises him—and by extension all pacifists—by stating: “Where would we all be if we decided to think that way?” The exchange anticipates a real life debate that would erupt in 1961 over whether a man should have the right to protect his fallout shelter with firearms.

The scene from the book in which Gladys has taken her radiation-sick daughter Ginny to the hospital is also drained of its power. We don’t see the strain on the health care providers that we glimpse in the novel. And the radiation-scarred little boy who repulses Gladys and Ginny in the book looks like an adorable, though heavily bandaged, moppet in the television adaptation.

The TV version differs significantly from the novel in that Jon Mitchell, Gladys’s husband (seen briefly at the breakfast table as the program begins), does not return home in the end. In one genuinely dramatic scene Gladys learns of her husband’s death from Jon Mitchell’s secretary who informs her that she was speaking with him on the phone when the line went dead at the time of the attack.

The persistent radio reports (on a Motorola radio, of course) featured in the book remain mostly intact for the adaptation. It is worth noting that these dispatches are voiced by John Daly, the CBS radio reporter who, in real life, was the first broadcaster to announce the Pearl Harbor attack on June 7, 1941.

Just as the novel does, the TV program includes a final radio report that all but certifies America has won the war (the book left zero doubt about who won the war):

“This is official, a bulletin from General Headquarters. It is reported that our planes are now able to fly over enemy territory almost at will. It is expected that we will soon land ground forces on a number of enemy beaches. I repeat: The enemy’s will and ability to fight have now virtually been broken. That is all for the present.”

The last scene in Atomic Attack is especially syrupy and hard to watch. Five-year-old Ginny asks “Are we winning, mommy?” To which the newly widowed Gladys replies strongly: “Not yet, darling, but we’re going to. I promise you that, dear Ginny, we are going to win.” The annoyingly cheerful Ginny replies, “I’m so glad, mommy.”

And in case anyone in the audience missed or doubted the propagandistic quality of the show, the end credit narration eliminates any uncertainty:

“We wish to thank the New York State Council of the City Civil Defense office and national Civil Defense headquarters in Washington for their kindness in providing technical information and advice throughout the presentation of tonight’s show Atomic Attack.”

EXCERPTED REVIEWS – THE BOOK, “SHADOW ON THE HEARTH”

“The newest entry in the perpetual good-gracious-what-next! sweepstakes is Judith Merril’s Shadow on the Hearth, a rather chintzy account of what happened to a Westchester family when the atomic bombs began to burst through the American air in some atomic war of tomorrow.

I always feel a profound sympathy for Westchester people, and I was deeply distressed when spectacularly unpleasant things began to happen to Gladys Mitchell, an attractive young matron of 37, her husband, Jon (repeat, Jon, not John), and her two daughters, Barbie, 15, and Ginny, 5—who once more confirms my belief that nowadays there’s no such thing as a completely implausible child in fiction or an incompetent child actor on the stage. Is there?”

The New York Times

06/15/1950

Byline: Charles Poore

“It is remarkable that it has not occurred to other writers that this awesome and frightening story could be best told by a woman and preferably a suburban housewife. A man inevitably would be forced into action outside the home…In this novel the action is entirely within the walls of a house; the terror comes only through radio and telephone.”

The Saturday Review

07/29/1950

Byline: Harrison Smith

“Gladys Mitchell, who had paid little attention to world affairs, wavers between bravery and hysteria as she steers her family through the days following an atomic attack on the U.S. She alternately obeys and resists official instructions, nurses her daughter through radiation sickness, shelters an innocent scientist wanted by security police, and helps fight off looters. The war is brief and the U.S. is victorious. The situations are a little pat, and the mother vaguely stupid, but this is a fairly successful woman’s story with a timely atmosphere.”

Booklist

07/15/1950

Byline: No Attribution

“Miss Merril’s story has the immediacy of today’s events; it is plausible, tense, sometimes comes close to approximating the hysteria such a catastrophe might bring upon thousands of people… Miss Merril makes a deliberate attempt to put readers into Gladys Mitchell’s place, to make them see and hear and feel her world just before and after the bombs came.”

Chicago Tribune

07/02/1950

Byline: August Derleth

“No cosmic spectacle here, but a novel of intimate immediacy and everyday urgency, quietly terrifying and deeply moving—and handled with a skill astonishing for a first novelist.”

Chicago Sun

08/08/1950

Byline: No Attribution

“This novel exists pretty much in a vacuum. While the author tries very hard to show the plucky suburban housewife struggling gamely to out-Mrs. Miniver Mrs. Miniver the whole business seems little more than a somewhat inconvenient escapade. The characters who drop in from time to time seem shadowy figures whose motivation is unexplained.”

The San Francisco Chronicle

08/27/1950

Byline: I.B.

“Judith Merril does almost too convincing a job. The suspense is almost unendurable, not only because of the trials and struggles of the characters but because it is dreadfully easy to put yourself in their place and feel the terror and frustration and helplessness of the civilian whose home is suddenly turned into a battlefield.”

The Oakland Tribune

09/03/1950

Byline: Nancy Nye

“Whatever else may be said of Judith Merril’s narrative ability, she has struck a most timely hour to publish Shadow on the Hearth. Her details of the Mitchell household and of the civilian-defense handling of the emergency are convincing, a readable slice of imagination.”

The Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Gazette

07/30/1950

Byline: H.G.

“Miss Merril has handled her spine-chilling story very well, on the whole.”

The Charleston (West Virginia) Gazette

06/25/1950

Byline: Mary Chilton Chapman

EXCERPTED REVIEWS OF THE TELEVISION PROGRAM “ATOMIC ATTACK” (MOTOROLA TV HOUR)

“Most damaging of all to the power of this drama was its conclusion. Our brave suburban mother was informed by John Daly over the radio (how did he survive?) that we had plastered every key city in the Soviet Union (CONELRAD Editor’s Note: The reviewer is in error on this point as the name of the enemy is never mentioned in Atomic Attack) with hydrogen bombs, that our airborne troops had landed in its territory, and that the enemy’s will to resist had entirely died.

‘Are we winning?’ asks her little daughter eagerly. ‘Are we winning, Mother?’

‘Not yet, darling,’ says her mother, gazing into space, ‘But we will – we will win -’

I am sure a man of (teleplay writer David) Davidson’s intelligence meant this ‘winning’ as a victory of human courage over catastrophic, but I am not at all sure that this is what ABC or Motorola meant, or what millions of viewers understood. Here was the massive retaliation we have been hearing about: If they get us first, we’ll get them next. Our major cities are destroyed, according to the script, and now all the enemy’s major cities are destroyed. Are we to be comforted because two civilizations are in ashes?

This was the real moment of horror: the word ‘win.’”

The Reporter

06/22/1954

Byline: Marya Mannes

“The most effective portion of Atomic Attack was in its opening act of twenty-odd minutes. The Mitchell family of Westchester has had breakfast and started on their normal day. The father has gone to New York, the two children are off to school and Mrs. Mitchell is beginning her day of household chores. Then the bomb comes.

The wife’s lack of preparedness as shown in the play constituted an exceptionally valuable and dramatic instruction in the importance of civil defense: The things that should be done and the article that should be on hand for just such an emergency were spelled out. Every family watching must have associated with Mrs. Mitchell’s plight and instinctively thought of their own lack of preparation. The civil defense program seldom has had a more articulate advocate than in Atomic Attack and for that alone the program was worth the doing.”

The New York Times

05/21/1954

Byline: Jack Gould

“With Phyllis Thaxter starred, the Mororola TV Hour on ABC-TV last week (18) presented Atomic Attack, a fictionalized documentary concerning the dropping of a hydrogen bomb on New York and effects of the destructive blast on a Westchester family. It was a frightening reminder of what might be in store for us, but for all its educational values, the show failed to come alive, and it never went beyond the limited boundaries of standard – and rather trite – TV melodrama.”

Daily Variety

05/26/1954

Byline: Hift.

ATOMIC ATTACK: THE ENTIRE TELEVISION FILM IN FIVE PARTS

1 comment:

I'm using AVG antivirus for a couple of years now, and I would recommend this solution to everyone.

Post a Comment